Controlled Vocabularies, Part II

A Practical Builders Guide

Every organization speaks its own language but many organizations do not have controlled vocabularies. Language within organizations is how we communicate with each other and machines. But often agreeing upon language is embedded in company culture, a strange and wild landscape cluttered with the creative lingo of marketing and branding, the complex nuances of technical terms, business concepts, acronyms, and domain-specific jargon, that evolves organically over time.

This goes without saying but language, and for that matter, vocabularies are influenced by company culture and are inherently political. When immersed in the daily grind of work, humans often lose sight of how internal, organizational language and vocabularies drift from delivering true semantics, the art of detailing the context and meaning of words and language.

That acronym everyone throws around as the piece-de-resistance of a company initiative? Yeah, that acronym means nothing if not well defined and associated with its actual definition and spelled out nomenclature. When this language remains undocumented, unstructured and ungoverned, it becomes a source of confusion, inconsistency, and lost productivity. That’s where a controlled vocabulary can deliver immense value in context engineering efforts. Controlled vocabularies guided by the SKOS data model and ontology, further lends a systematic approach to managing terminology and can transform how your organization communicates, searches, and makes sense of information.

What Is a Controlled Vocabulary?

A controlled vocabulary is a curated collection of terms and concepts used consistently across an organization. Unlike natural language, where multiple words can mean the same thing and the same word can mean different things, a controlled vocabulary establishes preferred terms, defines relationships between concepts, and creates a shared understanding of what words mean in your specific context. You’re organizing, pruning, and cultivating the terminology that already exists within your organization.

Discovery: Finding the Terminology That Already Exists

Before you can control your vocabulary, you need to discover it. Organizations rarely start from scratch; terminology is already embedded in countless systems and documents. The challenge is extracting candidate concepts systematically. Your first concept mining efforts will focus on the systems that already contain terminology. Let’s explore these common sources.

Data Catalogs

Data catalogs are goldmines of organizational vocabulary. They contain table names, column names, dataset descriptions, and business glossaries. Extract these systematically, paying attention to naming conventions and patterns. A column named `cust_acq_dt` tells you that your organization uses abbreviations for “customer acquisition date.”

I hope we realize by now, that the label ‘cust_acq_dt’, while meaningful within an organization, lacks true semantics. The naming convention “cust_acq_dt” is typically called abbreviated or truncated naming, often seen in database schemas and legacy systems. It’s a form of snake_case (using underscores to separate words) combined with heavy abbreviation.

The label isn’t semantic because it sacrifices readability for brevity:

“cust” instead of “customer”

“acq” instead of “acquisition”

“dt” instead of “date”

A semantic label is self-documenting and immediately understandable without context, like customer_acquisition_date or even better in some contexts: customerAcquisitionDate (camelCase) or CustomerAcquisitionDate (PascalCase). It is recommended that a semantic label in a controlled vocabulary be formatted in sentence case or title case, if a formal noun. Best practices favor semantic, self-documenting names since storage is cheap and code readability/maintainability is more valuable than saving a few characters. See the label formatting guidance in ANSI Z39.19 for a more detailed explanation.

Database Reference Tables

Database reference tables are fabulous sources for terms and concepts. Look for lookup tables with codes and descriptions—these are controlled vocabulary concepts hiding in plain sight. A `product_status’ reference table with values like “ACTIVE,” “DISCONTINUED,” “PENDING” represents decisions someone already made about how to categorize products.

Metadata Repositories

Metadata repositories like data dictionaries, business glossaries, and enterprise architecture tools contain concepts and sometimes, formal definitions and relationships between concepts. These are authoritative sources that can anchor your vocabulary, if leveraging metadata to support interoperability and integration patterns.

Collaboration Platform Taxonomies and Vocabularies

Collaboration platform taxonomies and vocabularies, like those found in GitHub, Confluence, and SharePoint, contain rich organizational structures that reveal how your teams naturally categorize knowledge. GitHub repositories use topics, labels, and organizational hierarchies that reflect how engineering teams think about projects, technologies, and domains. Repository names, branch naming conventions, and issue labels form an emergent taxonomy of technical concepts. Confluence spaces and page hierarchies show how documentation is organized, with page titles, labels, and space categories revealing business and technical terminology. SharePoint sites, document libraries, and metadata columns expose how different teams structure their information—folder hierarchies often represent functional or process-oriented taxonomies that have evolved organically.

These common collaboration platforms also contain invitation trees—the structural relationships between spaces, repositories, and sites that show how knowledge domains connect and subdivide. A parent Confluence space for “Product development” might contain child spaces for “Mobile apps,” “Web platform,” and “API services,” revealing both terminology and conceptual relationships. Mining these invitation trees through APIs or via manual CSV downloads provides a ready-made hierarchical structure that reflects actual usage patterns.

The tags and labels users apply to content across these platforms are particularly valuable because they represent folksonomy—the vocabulary people organically use when categorizing their own work. While not as controlled as formal taxonomies, these crowdsourced tags reveal synonyms, variations, and emerging concepts that formal vocabularies might miss. Extract these tags and folksonomies, analyze tag frequency and co-occurrence, and use them to validate or enhance your controlled vocabulary with concepts that reflect how people actually work.

Corpus Analysis: Learning from Actual Usage

While structured systems tell you what should be used, analyzing actual content reveals what is being used. Document Analysis is part of corpus analysis, and involves scanning reports, specifications, policies, and other organizational documents to identify frequently occurring terms and phrases. Simple frequency analysis reveals what concepts matter most to your organization. If terms and concepts are discovered with a high degree of frequency, they are likely to be welcome candidate concepts for a controlled vocabulary. Set a frequency threshold, so that you gather terms that are at or above XX frequency, as part of a document analysis strategy for candidate concept harvesting.

Natural Language Processing

Natural Language Processing (NLP) takes this further. Modern NLP techniques can extract named entities (people, places, organizations, products),iIdentify noun phrases that represent concepts, recognize multiword or compound terms that function as single concepts, detect acronyms and their expansions and find synonymous terms through distributional similarity. Tools like spaCy, NLTK, or cloud-based NLP services can process thousands of documents to surface terminology patterns. Pay special attention to noun phrases that appear frequently in similar contexts—these are likely important organizational concepts.

User Search Queries

User search queries in search and query logs reveal how people actually look for information. Search logs from your intranet, document management system, or data catalog show the vocabulary gap between what users think and what your systems understand. These query logs might highlight common internal biases—when internal perceptions about concept importance or concept meaning do not match external customer search logs. User search queries account for internal, domain systems in addition to search logs sourced from external sources. Mediating the balance of sources is critical for the integrity of any vocabulary.

Stakeholder Interviews

Stakeholder Interviews remain invaluable. Subject matter experts carry domain knowledge that doesn’t exist in any system. Ask them about the terms they use daily, the distinctions that matter in their work, and the concepts that newcomers struggle to understand. Often, taxonomists, ontologists and metadata professionals use tools such as card sorting and tree testing to gather stakeholder input, and deconstruct language and vocabularies.

Stakeholders are the people using terms and concepts in context, and are important input sources for validating vocabulary concepts such as what should be a preferred label and what concepts should exist as alternative labels. Stakeholders are also helpful for understanding the relationship between concepts, relative to workflows and to help form definitions for concepts.

Existing Standards

Existing standards in your industry provide ready-made vocabularies. Why reinvent terms for financial instruments, medical procedures, or chemical compounds when international standards already exist? Leverage industry ontologies, classification systems, and standards as starting points. Some interesting standards of note:

SNOMED CT: Terminology and standard for exchange of clinical health information

NIST-NICE Framework: Skills, roles and general workforce competencies

ESCO: European skills, competences, qualifications and occupations

Google Product Taxonomy: For online commerce

EU AI Taxonomy: Structured hierarchy of concepts describing AI systems

There are tons of open SKOS vocabularies on the open web that are very useful for modeling domains and defining concepts.

Application Schemas

Application schemas contain field names, dropdown options, and validation rules that represent vocabulary decisions. An expense management system’s list of expense categories is a controlled vocabulary for spending types.

Integration: Combining Multiple Sources

You’ll inevitably discover the same concepts from multiple sources, but expressed differently. This is where the real work begins and involves tracking provenance, understanding where a candidate concept comes from and its intended use in the source system. Because context does rely upon provenance, document where each term came from, before merging anything.

Provenance Matters

To track provenance and context, create a simple provenance tracking system. This can be as simple as reading columns is a spreadsheet, to document the necessary provenance information. This documentation is critical as it is helpful for informing disambiguation needs and settings. Using the example below, it is very likely that Customer acquisition cost carries a unique definition, meaning and context and its use as a concept will likely be specific to the finance side of the business.

Candidate concept: Customer acquisition cost

Source: Finance Data Warehouse

System: Oracle ERP

Date Extracted: 2025-10-15

Authority: Finance Department

Definition Source: CFO Policy Document 2023-06

By collecting basic provenance, future semantic work such as maturing a controlled vocabulary into a taxonomy or modeling the future ontology will also be easier, as the source, system and authority for concepts is at the ready, adding the essential context needed for vocabulary design decisions.

Provenance also matters because it helps resolve conflicts, such as which definition is authoritative or should there be two disambiguated concepts for context-specific representations. Provenance also lays a foundational governance element, documenting the source and system for any term or concept, answering the question, who owns this term?

By documenting provenance, traceability is enabled, to detail where a term is actually used. Finally, provenance supports impact analysis, so we are eyes wide open as to what breaks if we change this term.

Resolving Duplicates

When the same concept appears with different names across sources, you need a resolution strategy. Exact duplicates are easy—same term, same meaning. Just consolidate and retain all provenance records. When we start to account for synonyms, acronyms and misspellings, we are required to choose a preferred term, if following the SKOS data model logic.

To build a robust controlled vocabulary, appoint one preferred term and as many alternative terms as necessary, to account for all of the ways a preferred term can manifest, alternatively. Alternative labels can include synonyms, acronyms, misspellings. This is where we start modelling coverage or enriching coverage models. Coverage models ensure that we capture as many expressions for any given thing within our systems.

In making these decisions and modeling semantics, take into consideration official policy or regulatory requirements, frequency of use across the organization, term semantic quality such as clarity, alignment with industry standards , and technical vs. business language preferences. For example, if you find “Customer acquisition cost,” “CAC,” “Cost to Acquire,” and “New Customer Cost” across different systems, you might choose “Customer acquisition cost” as the preferred label because it’s clear, complete, and widely understood.

Handling Homonyms

Handling homonyms (same term, different meanings) is trickier. A “customer” might mean different things to Sales (potential buyers), Finance (accounts receivable), and Support (service recipients). Don’t force them to reconcile when the base, contextual definitions of each instance is unique. Create distinct concepts with context qualifiers: “Customer (Sales prospect),” “Customer (Account),” “Customer (Support case)”. By doing so, concepts are disambiguated and concept context is inferred.

Partial Overlaps

Partial Overlaps represent concepts that are similar but not identical. “Employee” and “Staff member” might seem synonymous, but in some organizations, contractors are staff members, not employees. Clarify the boundaries through careful definition.

Consider the circular synonym problem illustrated by variations like “cuisinart,” “cuizinart,” “food processor,” “blender,” “kitchenaid,” and “kitchen aid.” These terms have overlapping but distinct meanings—some are brand names, some are product types, some are misspellings. Your controlled vocabulary must decide: Is “Cuisinart” a preferred term for the brand, with “food processor” as a separate concept for the product type? Map these relationships explicitly, designating terms according to their preferred utilities.

Definitions: Giving Terms Precise Meaning

A controlled vocabulary without definitions is just a list of words, and is only semantic to humans, by way of text labels. Definitions transform terms into concepts with precise boundaries. The controlled vocabulary concepts plus associated definitions and altLabels must then be encoded, using metadata schemas and ontologies, to serve up semantics for machines. This is why SKOS is so powerful for modelling concepts and controlled vocabularies: we are leveraging a W3C compliant data model standard and technically, an OWL FULL ontology.

Writing Effective Definitions

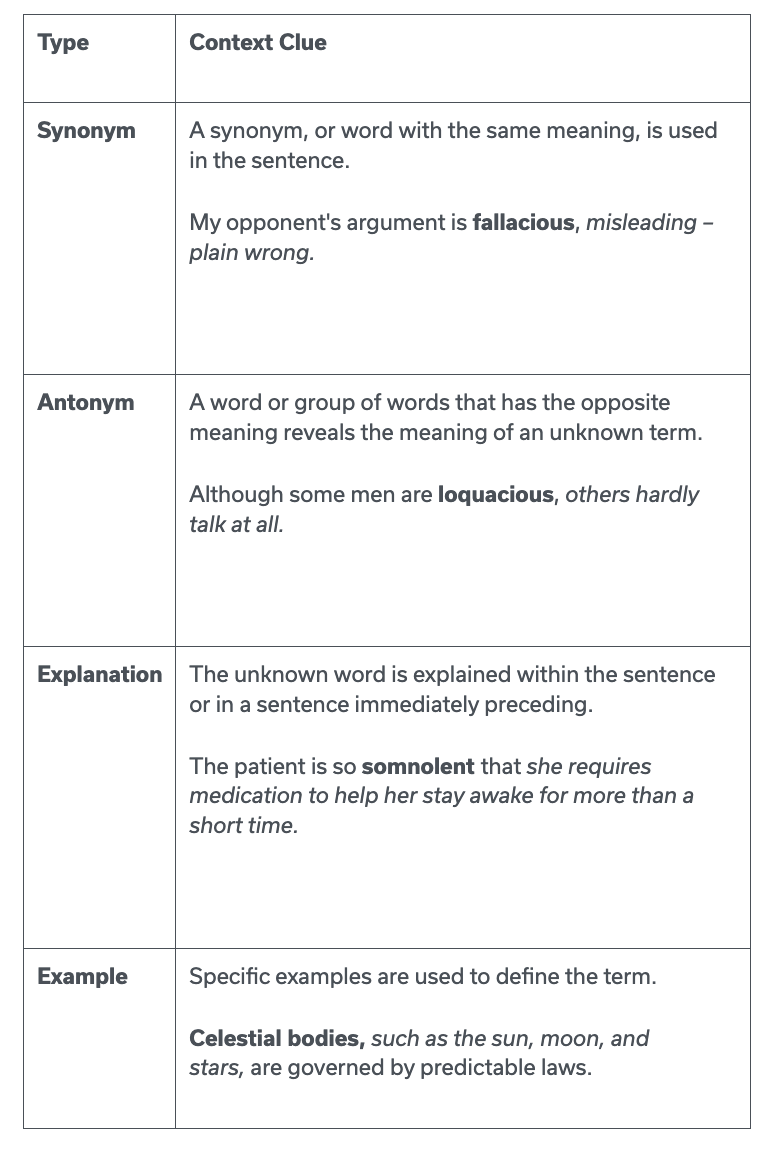

A slight detour here, a preamble, before digging into the nuts and bolts of definitions. Effective definitions provide rich descriptive context, enabling genuine understanding for machines and humans. Within the realms of cognitive and learning science principles, well-crafted definitions embed context clues, to guide interpretation through four key mechanisms: synonyms that offer alternative expressions, antonyms that establish boundaries through contrast, explanations that unpack complex concepts into comprehensible components, and examples that ground abstract ideas in concrete instances. These contextual elements transform definitions into dynamic, purpose-built context-rich nuggets, that actively facilitate comprehension and semantic processing.

Context Clues

To make a good definition a great definition embed context clues. Context clues are part of teaching reading competencies to humans. Clues are textual hints, embedded within surrounding words, sentences, or paragraphs that enable readers to decode unfamiliar terms without consulting external references. By providing definitions, synonyms, antonyms, or illustrative examples, these linguistic signals guide readers toward understanding new vocabulary through inference rather than interruption. This decoding strategy forms a cornerstone of effective reading comprehension, empowering readers to maintain flow and grasp meaning efficiently as they navigate through complex texts.

This may seem like a big “so what? What does this have to do with semantics?”. But think for a minute what we are doing when we engineer context. We are engineering context clues to guide LLMs through a quagmire of text, code and infrastructure workflows. A SKOS controlled vocabulary is a context clue framework. We structure our vocabularies to encode machine readable and interoperable context rich with context clues. Each concept imbues context via synonyms (altlabels and hiddenLabels), antonyms (a custom class label can capture this characteristic), explanation (the concept itself, definitions and linked data authority files) and example (definitions and other documentation properties such as skos: example and skos: scopeNote ).

SKOS, being an RDF-based vocabulary, can be rendered in any RDF serialization format.This can be presented to LLMs and machines as RDF/XML, Turtle, JSON-LD, RDF/A, in addition to a few other formats. This means that by building a SKOS vocabulary with proper text definitions, you are engineering context. Context engineering with SKOS means taking the time to formalize text definitions, rich with context clues. This effort may seem to be a tad extra, but I promise well formed definitions will go a long way in stitching the context fabric, valuable for humans and machines. There are several wins I could expound upon, but I will reserve this diatribe for another article.

Back to Definitions

SKOS definitions deliver direct explanations of concepts, using context clues. by providing explicit meaning for concepts, similar to how a textbook defines a term, allowing LLMs to understand that a “customer” with the definition “an individual or organization that purchases goods or services” refers to a buyer relationship rather than other potential meanings like “customs officer” or “customizer.”

Definitions do not work with the concept preferred label alone. We are building each concept to exist as a robust concept record. Remember, alternative labels in SKOS function as synonyms which become restatement context clues for machines and humans. By teaching AI systems to learn that when they encounter “client,” “buyer,” “purchaser,” or “patron” in text, these are semantic variations of the same concept represented by the preferred label “customer”.

This semantic concept enrichment enables better entity recognition and disambiguation across diverse vocabularies. The combination of preferred labels with their alternatives and definitions creates a rich semantic fingerprint that helps LLMs recognize concepts through pattern matching. When an AI system encounters text about “purchasing,” “buying,” or “commercial transactions,” these encoded contextual semantics provide the inference clues needed to correctly identify and link to the “customer” concept even when the exact preferred label isn’t present in the text.

Genus-Differentia

To form reliable, descriptive definitions, start with the Genus-Differentia Structure for any given concept. This means determining the broader category (genus), and then specifying what distinguishes this concept (differentia) from its genus. “Customer acquisition cost is a financial metric that measures the total cost of acquiring a new customer, including marketing and sales expenses.” This is an especially helpful approach because Gens-Differentia helps to define concepts in context, and becomes the prework for future taxonomies, thesauri and ontologies. Take note of potential future relations that will not be accounted for directly, in controlled vocabularies.

Circularity

Next, avoid circularity. Don’t define terms using the terms themselves. “Customer churn is when customers churn” tells us nothing. Add detail and define in-context usage or context relevant to systems. Use simple language, also known as plain language. Definitions should clarify, not obscure. Avoid jargon in definitions unless the act of defining is to define jargon. Simple, descriptive language goes a long way, when definitions also serve to disambiguate concepts.

Scope and Boundaries

Specify scope and boundaries by detailing what a concept definition excludes and includes. For example, “employee includes full time and part-time staff with formal employment contracts. It excludes contractors, consultants, and temporary workers.” Detail the intended coverage of the concept by explicitly stating the scope and boundaries within the definition, thereby helping users and machines to understand how best to make sense of a concept, its intended use and semantics.

Provide Context Clues

Enrich definitions by providing context clues, as part of each definition. While the context can also be documented as part of a documentation property such as SKOS: scope note, adding more rich context and usage guidance as part of a definition is helpful as this effort also helps to establish scope and boundaries for concepts.

I personally like to document organizational and domain context as part of the definition during the controlled vocabulary building stage, and only separate the usage guidance into a scope note field when at the taxonomy building phase. This is only for simplicity sake, so as to not introduce multiple schema fields while curating candidate concepts.

Authority Files and Linked Data

Finally, go the extra mile with authority files. Link authority files that lend confidence and validity to concept definitions. I like to call this “touching grass” for concepts. Authority files may be HTTP or HTTPS URIs, that can be encoded as “SKOS: exactMatch”. A form of linked data, the authority file can be an internal, reliable source used to define a concept or an external source.

Linking to an external authority file like DBpedia provides a canonical, globally unique identifier for the concept “customer,” ensuring that different systems referring to this URI are talking about the exact same concept regardless of local variations in terminology or language. To boot, sources like DBpedia have ontology backbones and are knowledge graph architectures.

Authority files sourced from ontology-bolstered sources such as DBpedia, VIAF, The Getty and Wikidata, supplies machine readable, standardized definitions, multilingual labels, and related concepts (broader/narrower/related terms). Creating a shared understanding via authority files prevents semantic drift and reduces ambiguity across different applications and datasets. By referencing DBpedia’s rich contextual information—including the concept’s relationships to other entities, historical usage, and domain-specific variations—systems can inherit validated semantic knowledge without having to redefine or maintain this conceptual framework independently.

Definition Sources

Document where definitions come from. This step is critical for operationalizing vocabularies and for gathering data about concept constraints and guidelines. Typical definition sources include regulatory requirements, industry standards, internal policies, subject matter expert input, documentation of common usage within the organization, and authority files. When sources conflict, make choices based on authority, applicability and historical usage of concepts. A regulatory definition usually trumps internal preference and the languages of brand and marketing. You may always create a custom class concept to represent the “display label” or front matter if marketing and branding insists on an ambiguous concept name that does not match the more widely known meaning of a thing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Intentional Arrangement to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.