The Governance-Semantics Disconnect: A Systemic Problem

Perhaps the most fundamental flaw in enterprise metadata management approaches are the organizational divides between governance and semantic design. In most enterprise architectures, data governance teams focus on compliance, quality metrics, and business process alignment, while semantic concerns are relegated to technical teams implementing search interfaces or analytics tools. This separation creates what information scientist Marcia Bates calls "semantic fragmentation"—where the rules governing data have no meaningful connection to the conceptual models that should give that data meaning.

The Separation of Concerns is Not Helping

Library science demonstrates why this separation is systemically harmful. In library metadata systems, governance and semantics are inseparable: cataloging rules like RDA don't just specify data quality requirements, they embed rich semantic relationships directly into the descriptive process. When a librarian applies RDA rules to describe a resource, they're simultaneously enforcing data quality standards and building a conceptual model that connects that resource to broader networks of meaning. As library metadata expert Barbara Tillett explains, "Every cataloging decision is a semantic decision—there is no such thing as 'neutral' metadata governance".

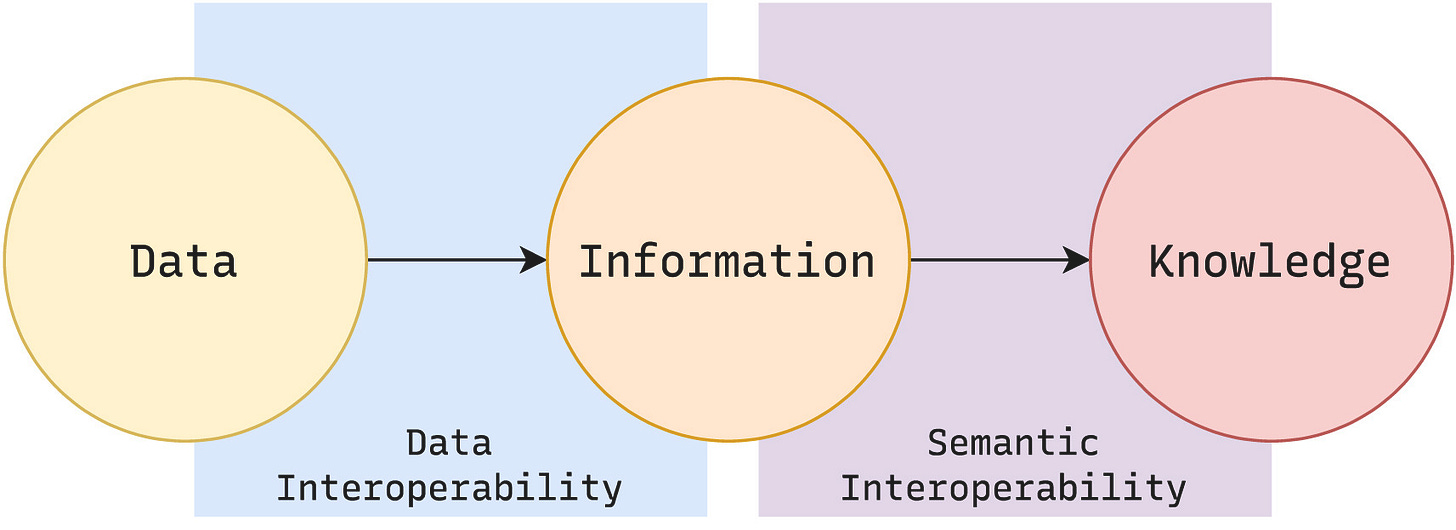

This integration is why library systems achieve genuine interoperability across institutions. When two libraries both follow Dublin Core or RDA, they're not just ensuring consistent data entry—they're building compatible conceptual models that enable the meaningful exchange of data. Enterprise systems that separate governance from semantics produce what appears to be clean, well-governed data that nonetheless remains semantically opaque and impossible to integrate meaningfully across system boundaries.

Data Models as Semantic Infrastructure

The absence of true data modeling in enterprise metadata systems reveals itself most clearly in failed integration projects. Organizations spend millions on data integration platforms, master data management suites, and semantic layers, yet struggle to achieve basic interoperability between business units or external partners. The problem is not technical—it's conceptual. Integration becomes an endless exercise in mapping between incompatible worldviews when organizations lack shared data models that define both entities and their semantic relationships.

And let me reiterate, this does not mean one data model to rule them all.

Library science's successes with interoperability stems from its commitment to explicit data modeling as the foundation of semantic systems. FRBR, for instance, doesn't just define four entity types (Work, Expression, Manifestation, Item)—it specifies the semantic relationships between them and provides rules for how those relationships should be interpreted and maintained. This creates what metadata theorist Michael Gorman calls "semantic scaffolding": a conceptual framework that enables both human catalogers and machine systems to make consistent, meaningful decisions about how to organize and relate information.

Enterprise systems that skip this modeling step, treating metadata as labels rather than relationships, inevitably hit semantic walls. A "customer" entity in one system may seem equivalent to a "client" entity in another, but without explicit modeling of what these terms mean, how they relate to other concepts, and what semantic constraints govern their use, integration remains superficial. The result is what appears to be unified data that actually represents incompatible conceptual models underneath. Impossible to reconcile and thread through a data infrastructure.

The Label Trap: Why Semantic Layers Fall Short

Modern enterprise semantic layers, despite their sophisticated interfaces and natural language capabilities, often perpetuate rather than solve these fundamental problems. Tools that promise to "semanticize" enterprise data typically work by applying labels and descriptions to existing data structures without addressing the underlying absence of conceptual modeling. This creates what we will call `semantic theater’, systems that appear to provide rich meaning but actually just offer better search and visualization of the same semantically impoverished data.

The difference becomes apparent when these systems encounter the basic challenges that library metadata handles routinely: variant forms of names, changing organizational structures, multilingual descriptions, or temporal relationships. A semantic layer might successfully map "CEO" and "Chief Executive Officer" as equivalent terms, but it cannot address the deeper semantic question of how the concept of organizational leadership relates to other business entities, how it changes over time, or how it should be interpreted across different cultural or regulatory contexts.

Library metadata systems handle these challenges through what the late cataloging expert Sheila Intner calls "semantic architecture": explicit conceptual frameworks that define not just terms but the logical relationships and constraints that give those terms meaning in specific contexts. This is why library authority control systems can distinguish between "River" as a personal name and "River" as a geographic feature, or why BIBFRAME can represent the complex temporal and administrative relationships involved in serials (items published under the same title, generally as separate issues or annual texts) cataloging.

The Path Forward: Semantic-First Governance

The solution for enterprise metadata systems is not better labeling or more sophisticated search interfaces, but fundamental reorganization around semantic-first governance composites. This means designing data governance processes that begin with conceptual modeling, where every business rule and quality metric is grounded in explicit semantic relationships. It means treating controlled vocabularies not as afterthoughts but as foundational infrastructure, and designing system integrations around shared conceptual models rather than technical protocols.

Most importantly, it means recognizing that sustainable metadata systems require what library science has always understood: governance and semantics must be co-designed and co-evolved as integrated systems. Organizations that continue to separate these concerns will continue to struggle with the fundamental interoperability challenges that library science solved decades ago through patient, principled attention to metadata as intellectual infrastructure rather than technical convenience.

Thank you. What appreciate about "library science" for real-world business scenarios is conceptualizes a framework (before tech) that is understandable when have looked for a physical book in a library using metadata (even when did "not" know what metadata meant).

I love this! When we start peeling the layers of why systems are not compatible, the issue is not with the technology. We see that everything begins with governance and the conceptual model.