Process Knowledge Management, Part I

Accounting for How We Work

Introduction

Process engineering has traditionally been understood as the discipline concerned with designing, implementing, optimizing, and controlling industrial and organizational processes. Yet beneath this operational focus lies something more fundamental: the systematic capture and application of process knowledge—the understanding of how work flows, transforms, and produces outcomes within complex systems. As organizations increasingly rely on knowledge management infrastructure and artificial intelligence to augment human decisionmaking, process knowledge has emerged as a critical substrate that determines whether these technologies succeed or fail.

This essay examines process knowledge through the lens of knowledge management and semantic ecosystems, and states that the explicit representation of process understanding is an operational necessity, an epistemological foundation for trustworthy AI systems. The integration of process engineering principles with semantic technologies offers a pathway toward AI applications that are more capable, interpretable, auditable, and aligned with organizational intent.

The Nature of Process Knowledge

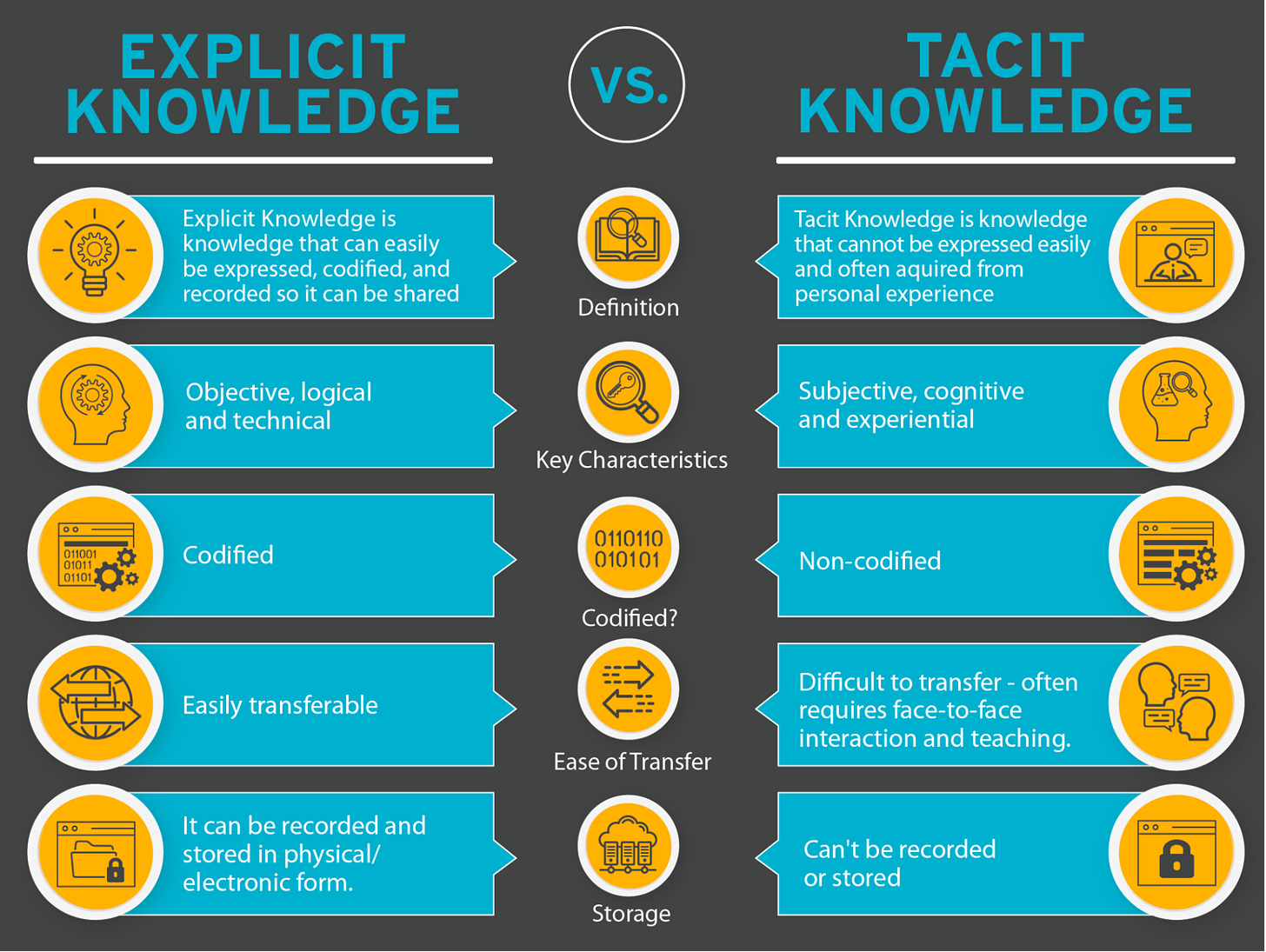

Process knowledge encompasses more than procedural documentation and workflow diagrams. It represents the accumulated understanding of why processes exist, how they interact with one another, what conditions trigger variations, and which outcomes indicate success or failure. Michael Polanyi’s distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge proves especially relevant here: much process knowledge resides in the practiced intuitions of experienced workers who navigate exceptions, recognize patterns, and make judgment calls that no standard operating procedure fully captures.

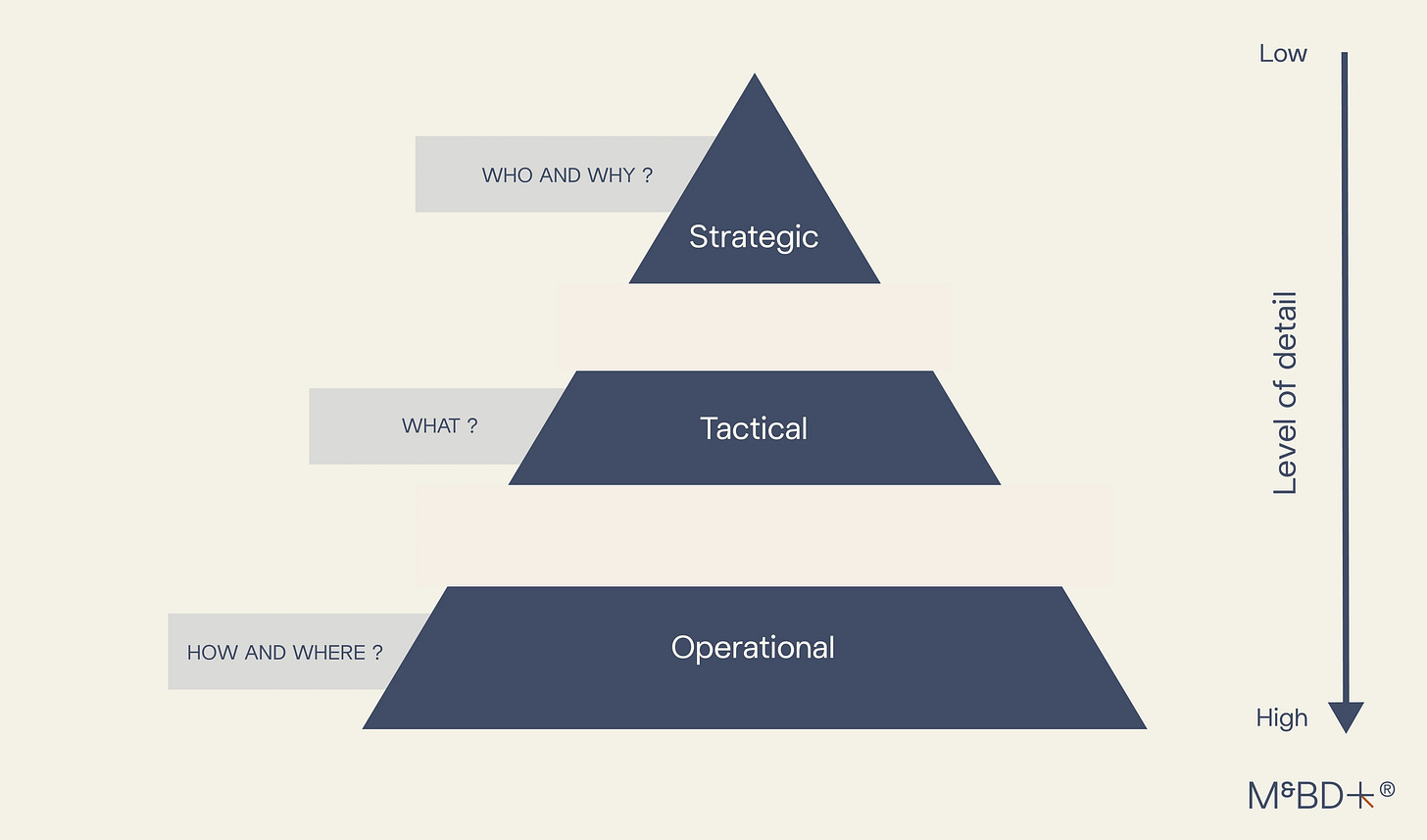

WithIn the context of a knowledge management framework, the challenge is to bring tacit knowledge to the surface without oversimplifying it into rigid rules. Process knowledge functions across various levels of abstraction. At the operational level, it clarifies the sequence and dependencies: determining the order of tasks and the conditions required to move forward. At the tactical level, it focuses on optimization and adaptation: managing resource allocation, identifying bottlenecks, and adjusting processes to meet changing needs. At the strategic level, it aligns processes with the organization’s mission: understanding the rationale behind processes, their contribution to value creation, and the trade-offs they involve.

Each of these levels requires different strategies for capturing tacit and explicit knowledge, as knowledge serves different stakeholders for varied use cases. For example, a product manager may need to manage concrete procedural guidance in the form of steps, stages, stakeholder ownership and measured outcomes. An infrastructure engineer may need systemic visibility into interdependencies. And an executive may need abstracted metrics that connect process performance to business outcomes. Knowledge management systems that fail to accommodate the multifaceted nature of process knowledge inevitably over index on one perspective, at the expense of others.

Because knowledge management is multidimensional and accounts for the tacit and explicit, the art of managing process is inherently non-linear, and cannot be captured from data points alone. Because all knowledge is not the same, process knowledge requires its own methodologies and practices so that process knowledge can be properly managed. Process knowledge, the type of knowledge AI workflows rely upon, requires unique and specialized practices, with the need for humans skilled in capturing, recording, representing and communicating its value streams.

Process Knowledge Frameworks

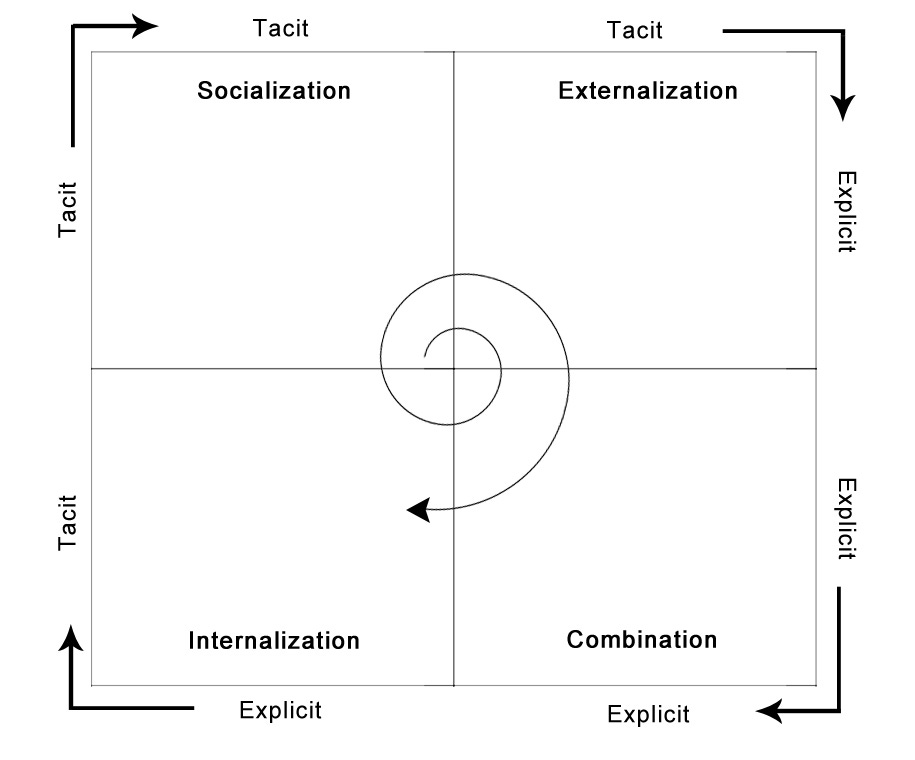

Knowledge management as a discipline has long grappled with the challenge of making organizational knowledge accessible, transferable, and actionable. The SECI model proposed by Nonaka and Takeuchi—describing cycles of socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization—offers one framework for understanding how process knowledge moves between tacit and explicit states. Process engineering contributes a complementary perspective by emphasizing the structural dimension of knowledge: how knowledge is organized, connected, and retrieved matters as much as what knowledge exists.

Traditional approaches to capturing process knowledge have relied on documentation, training programs, and mentorship relationships. These remain valuable, but they scale poorly and degrade over time as documents become outdated and experienced knowledge workers come and go. The emergence of enterprise content management, business process management systems, and more recently knowledge graphs has shifted attention toward encoded representations of process knowledge—representations that can be queried, validated, and reasoned over computationally.

This shift introduces both opportunities and risks. On one hand, encoded process knowledge can be versioned, audited, and propagated across systems with consistency that human-mediated knowledge transfer cannot match. On the other hand, the encoding process inevitably loses nuance, context, and the situated judgment that makes tacit knowledge valuable. The most sophisticated knowledge management approaches recognize this tension and design for hybrid systems where computational representations augment rather than replace human expertise.

Semantic Ecosystems and Process

Semantic technologies offer a particularly promising approach to process knowledge representation because they emphasize context, and meaning in addition to structure. Currently, the moniker for this flavor of documenting and codifying process knowledge representation, is referred to as context engineering. A hot, flashy AI job title, that in many instances, basically amounts to process knowledge engineering.

In AI engineering circles, the first three years have been focused upon trying to squeeze knowledge into relational database systems, and then heroically, wrestling the flattened, syntactic “knowledge” into shapes and forms suggestive of meaningful knowledge. But these tactics have proven to be largely unsuccessful, in delivering semantic knowledge representations, suitable for an LLM’s thirst for context and meaning. Traditional databases store data according to predefined schemas, in tables, columns and rows using syntax, mostly lacking the dimensions of knowledge necessary to satisfy context requirements.

Semantic representations using RDF, OWL, and related standards, express knowledge in a format that structures knowledge using ontologies to induce formal, logical reasoning, inference and explicit semantics. Because ontologies are flexible, breaking out of the programmatic constraints of a datastore, data warehouse or database, knowledge can be captured and represented, through rich, descriptive context. Ontologies are a lot like storytelling, able to capture carrying grades of knowledge, both tacit and explicit, if so designed. This distinction proves crucial for representing process knowledge, which is inherently dynamic and relational: processes connect inputs to outputs, actors to actions, conditions to consequences.

A semantic ecosystem for process knowledge typically comprises several interconnected layers. At the core lies ontologies— formal specification of the concepts, relationships, and constraints that define the domain. For process knowledge, this might include classes representing process steps, actors, resources, conditions, and outcomes, along with properties and attributes to add descriptors and characteristics such as conditions for processes and features of steps and stages. Relationships may include “precedes” “requires” “produces” and “governed by”, to denote how classes and properties are related to one another, with constraints detailing if a relation is direct, indirect, and expected data type and format for many values.

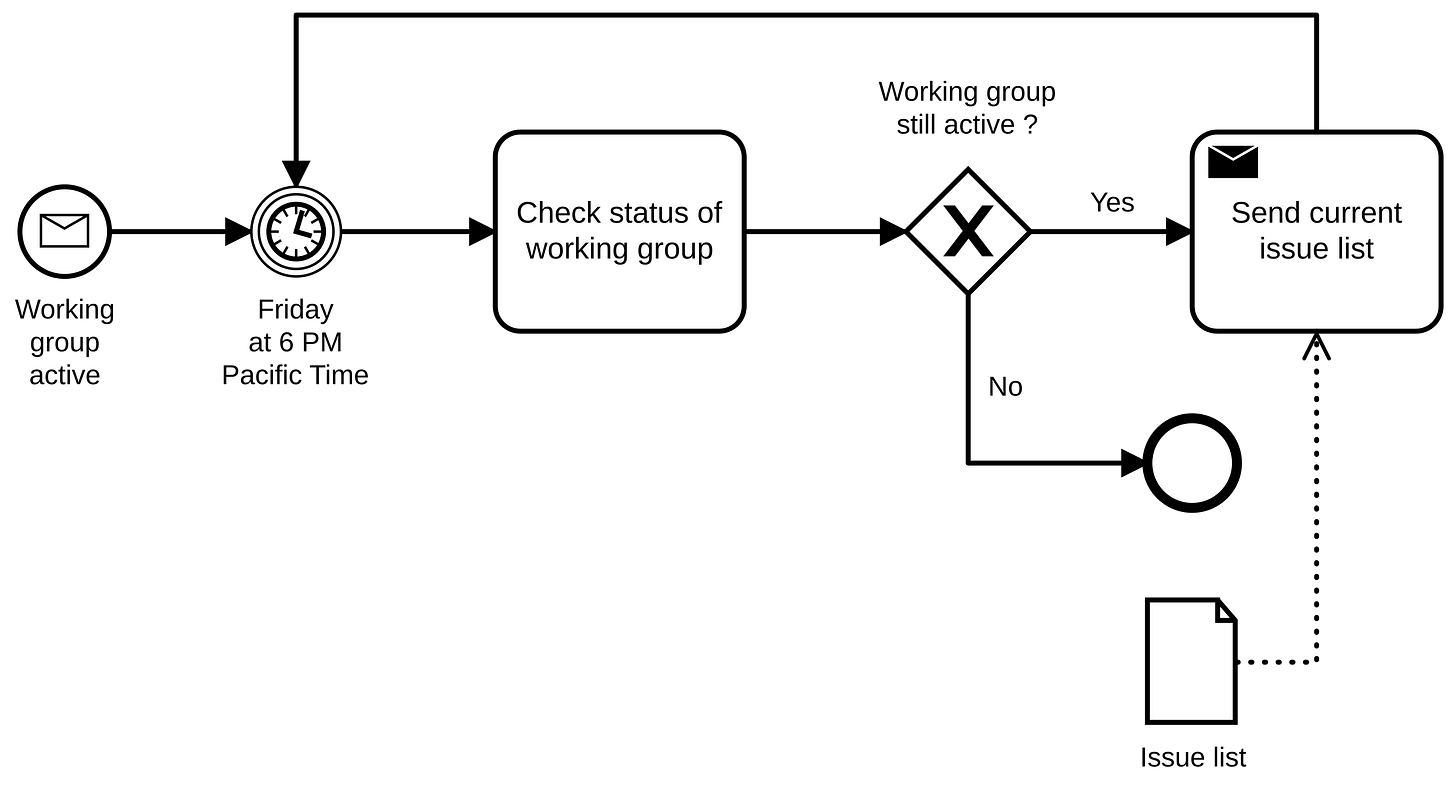

Standards like the Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) provide conventional vocabularies, but true semantic interoperability requires grounding these processes in formal ontologies that can be extended and specified for particular domains.

Above the ontological layer sits the instance data, the actual processes, resources, and relationships that exist within a specific organization. This layer connects abstract process models to concrete operational reality. A semantic approach enables queries that traverse both levels—the ontology core and the instances. An AI agent can discover “what steps comprise this process” (steps) “what processes involve this resource”(instances) or “what conditions have historically correlated with process failures” (analytical).

The value of semantic ecosystems becomes apparent when process knowledge must cross organizational boundaries or integrate with external systems. Semantic representations can be federated, enabling queries across distributed knowledge bases without requiring centralized data warehouses. They can also incorporate provenance information using ontology standards like PROV-O, tracking where knowledge originated, how it was derived, and who validated it. This provenance capability proves essential for maintaining trust in process knowledge as it propagates through complex organizational networks.

Foundation for AI Systems and Workfows

The relationship between process knowledge and artificial intelligence operates in both directions. AI systems increasingly consume process knowledge to inform their operations, while simultaneously generating insights that enrich organizational understanding of processes. Getting this bidirectional relationship right requires careful attention to how process knowledge is represented, validated, and integrated with AI capabilities.

Contemporary foundational AI systems, particularly large language models, excel at pattern recognition and generation but struggle with systematic reasoning about processes. They can describe processes fluently by way of statistical probability, but cannot reliably execute multi-step procedures, track state across complex workflows, or verify that outcomes satisfy specified constraints. This limitation stems partly from architectural choices—transformer models process sequences but lack explicit mechanisms for maintaining structured state—and partly from training regimes that optimize for next-token prediction rather than procedural correctness.

Process knowledge encoded as semantic structures, offers an elegant counterbalance to the next token, generative, statistical prediction machine that is modern AI. When AI systems can access formal, ontological process representations, they gain access to constraints and dependencies that guide generation toward valid outcomes. A language model generating a project plan can reference an ontology specifying that certain deliverables require completed prerequisites. A recommendation system can consult process knowledge to ensure suggested actions comply with regulatory requirements. The semantic layer acts as guardrails, channeling AI capabilities toward outputs that respect organizational, process knowledge logic.

Process knowledge ontologies also addresses the interpretability challenge that plague many AI applications. When an AI system’s recommendations can be traced to explicit process knowledge, stakeholders can evaluate whether the system’s reasoning aligns with organizational intent. The foundational AI black-box concern will always be present as long as we lack visibility into reasoning logic and chain-of-thought. But ontologies give back some measure of control because its outputs can be validated against a human-machine, shared understanding of how processes should work.

Its Not Easy, But it’s Worth It

Despite these promises, integrating process knowledge with semantic ecosystems and AI presents substantial challenges. The first challenge is knowledge acquisition. Extracting process knowledge from organizational practice and encoding it in formal representations requires significant effort from domain experts who often lack familiarity with semantic technologies. Process mining techniques can partially automate this acquisition, by analyzing event logs to infer process models, but the resulting models capture observed behavior rather than intended process logic, and they miss the tacit knowledge stored with experienced workers.

A second challenge concerns maintenance. Processes evolve continuously in response to changing requirements, technologies, and the competitive landscape. Semantic representations of process knowledge must evolve correspondingly, requiring governance mechanisms that keep formal models aligned with operational reality. Organizations that invest heavily in initial process modeling but neglect ongoing maintenance, find their semantic ecosystems degrading into unreliable artifacts that AI systems cannot safely depend upon.

A third challenge involves the boundary between process knowledge and the contexts in which it applies. Process knowledge is never context-free; the same process steps may have different implications depending on who performs them, what resources are available, and what external conditions prevail.

Semantic representations must capture this contextual sensitivity without exploding into unmanageable complexity. This is where strong process knowledge management frameworks are necessary, to address scope creep and knowledge capture strategies. From an implementation perspective, knowledge infrastructure architectures that include named graphs, reification strategies, and contextualized knowledge bases offer elegant solutions to protecting process knowledge boundaries.

Finally, there is the question of authority. When AI systems reason over process knowledge, whose understanding of the process takes precedence? Different stakeholders may hold legitimate but conflicting views about how processes should work. Semantic ecosystems must accommodate this pluralism—representing multiple perspectives and tracking their provenance—rather than imposing false consensus. This requirement connects process knowledge management to broader questions about organizational governance and epistemic justice.

Integrated Process Intelligence

The convergence of process engineering, process knowledge management, semantic technologies, and AI points toward a vision of integrated process intelligence, organizational capabilities that combine human expertise with computational reasoning to manage processes more effectively than either could alone. Realizing this vision requires investments across multiple dimensions.

At the technological level, organizations need infrastructure that connects process modeling tools, semantic repositories, and AI platforms. Open standards like RDF, OWL, and SPARQL provide a foundation, but practical integration demands attention to data pipelines, access controls, and performance optimization. Knowledge graph platforms that provide logical reasoners, combine semantic storage, include graph algorithms and machine learning capabilities, represents a promising development, though these platforms remain relatively immature.

At the methodological level, organizations need practices for acquiring, validating, and governing process knowledge. Methodology is mostly sociotechnical by nature, in order to capture tacit and explicit knowledge.Technical practices include modeling conventions, validation procedures, version control. Social practices address stakeholder engagement, expertise recognition, conflict resolution. The discipline of enterprise architecture offers relevant precedents, as does the library and information science approaches to controlled vocabulary development and metadata management.

At the cultural level, organizations need to cultivate appreciation for process knowledge as a strategic asset. This means investing in roles and capabilities specifically devoted to process knowledge management, creating incentives for knowledge sharing, and building organizational memory that persists across the rate of headcount turnover. Process knowledge and all knowledge, for that matter, must be recognized as foundational infrastructure for organizational intelligence.

Conclusion

Process knowledge is about improving how work gets done. Process knowledge management is concerned with collecting, storing, documenting, codifying, encoding and operationalizing this specialized form of knowledge, available for AI and reuse. Knowledge is complex and messy, mostly because we collect, organize, store and access knowledge in uniform ways. Each type of knowledge requires an understanding, that all knowledge is not the same. Process knowledge is extremely valuable, for its ability to communicate the “how-to-do-a-thing” to both humans and machines.

As you build AI workflows, ask yourself, “do I want AI to perform tasks that follow ordered steps and need organizational or personal knowledge to be successful?” If the answer is yes, you’re probably dabbling in process knowledge. And if that’s the case, you may need a process knowledge management framework, whose end goal is to structure process knowledge with rich semantic context, using ontologies.

Afterword

Phew-! I just fit FOUR hot AI buzzwords into a single sentence!

If you are reading this last sentence, right here, message me with the four buzzwords, and I will gift you a FREE LIFETIME subscription to this newsletter, Intentional Arrangement!

📚This is the first of three parts about process knowledge, ontologies and semantic architectures. Next essay will dive into building an ontology, focusing on the unique needs of process knowledge. Stay tuned!

About me. I’m an information architect, semantic strategist, and lifelong student of systems, meaning, and human understanding. For over 25 years, I’ve worked at the intersection of knowledge frameworks and digital infrastructure—helping both large organizations and cultural institutions build information systems that support clarity, interoperability, and long-term value.

I’ve designed semantic information and knowledge architectures across a wide range of industries and institutions, from enterprise tech to public service to the arts. I’ve held roles at Overstock.com, Pluralsight, GDIT, Amazon, System1, Battelle, the Oregon Health Authority, and the Department of Justice and most recently, Adobe. I built an NGO infrastructure for Shock the System, which I continue to maintain and scale.

Most recently I served as a Senior Information Architect at Adobe, where I developed content models, taxonomies ontologies knowledge graphs and autotagger, that support AI and machine learning models, contextual design, and structured content strategy. I’ve also collaborated with GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums) organizations and cultural institutions, including the Smithsonian Institution, Twinka Thiebaud and the Art of the Pose, Nritya Mandala Mahavihara, the Shogren Museum, and the Oregon College of Art and Craft.

Tangential remark: in 2014, I attended the ASIS&T conference and signed up for a Knowledge Management workshop, thinking it was related to taxonomy work. I was completely surprised and utterly delighted to discover that I was wrong and got to learn about a whole new field about finding, documenting, and cataloguing organizational talent so that companies could shuffle people into positions better suited for their skills instead of just firing them. (Ideally, that’s what it would be used for anyway.)

I love this! I am trying to understand more about semantic layers, and you made it so much easier to grasp the concepts. Thank you for the article :)