Relationships and Knowledge Systems

The Architecture of Meaning

We rarely think about this consciously, but every time we organize anything—a bookshelf, a database, a filing system, a website—we’re making decisions about how things connect. These decisions have consequences that ripple outward, shaping what we can find, what we can ask, and what insights remain forever hidden from us.

In human life, relationships are so natural we barely notice them. You’re someone’s daughter, someone’s colleague, someone’s neighbor. You know that your access to information, opportunity, and influence often depends less on what you know than on who you know—and specifically, how you know them. The same person might be your brother, your business partner, and your landlord simultaneously. Context determines which relationship matters in any given moment.

Information systems face the same basic challenges. Resources—web pages, documents, datasets, products, people, concepts—don’t exist in isolation. They gain meaning through their connections. A journal article becomes findable because it has subject keyword and is authored by, cites, and is published in. These relationships are the organizational infrastructure that makes the resource useful and finable.

What I want to explore today is how we think about these relationships—and how different knowledge structures (from simple hierarchies to sophisticated ontologies) give us different expressive power for representing them.

Five Perspectives on Relationships

When knowledge engineers analyze relationships, we typically consider them from multiple angles. Each perspective is valuable, and reveals something unique about how connections function in an organizing system.

The Semantic

The semantic perspective is the foundation, the starting place. Semantics ask: what does this relationship mean? When we say a document ‘is derived from’ another document, we’re making a claim about intellectual lineage. When we say a person ‘is employed by’ an organization, we’re describing a specific social and economic arrangement. The semantic perspective captures the conceptual content of the association—what it means to a human who may understand it.

The Lexical

The lexical perspective examines how we express that meaning in language. English gives us words like parent, employer, author. But many relationships require phrases: is employed by, has publication date, is related to. Different languages carve up relational space differently. The lexical perspective reminds us that our vocabulary shapes what relationships we can easily name—and therefore, what relationships we tend to notice and encode.

The Structural

The structural perspective looks at patterns. How are resources actually arranged? What’s adjacent to what? In a taxonomy, structure manifests as hierarchy—broader terms sit above narrower terms. In a network, structure emerges from connection patterns. Two resources might be structurally close (few hops apart) even if their semantic relationship is complex. The structural perspective reveals the topology of our knowledge organization.

The Architectural

The architectural perspective considers complexity. How many components does the relationship have? A simple parent-child relationship involves two entities and one connection. But real-world relationships often have additional dimensions:

temporal scope—when did this relationship hold?

certainty—how confident are we?

provenance—who asserted this?

The architectural perspective examines how much sophistication our representation can accommodate.

The Implementation

The implementation perspective asks practical questions. How is this relationship encoded? What syntax represents it? Where is it stored? A relationship might be semantically identical but implemented as a foreign key in a relational database, a triple in RDF, a property in a labeled property graph, or an XML element. Implementation choices have consequences for performance, interoperability, and maintenance.

These different vectors, where relationships play, are complementary and all taken into account when modeling knowledge. And different knowledge structures emphasize different perspectives.

Progressions and Expressive Power

The simplest way to represent relationships is through physical arrangement. Put related things near each other. This is how we organize physical spaces—cookbooks in the kitchen, gardening tools in the shed. Proximity implies relationship, though the nature of that relationship remains implicit.

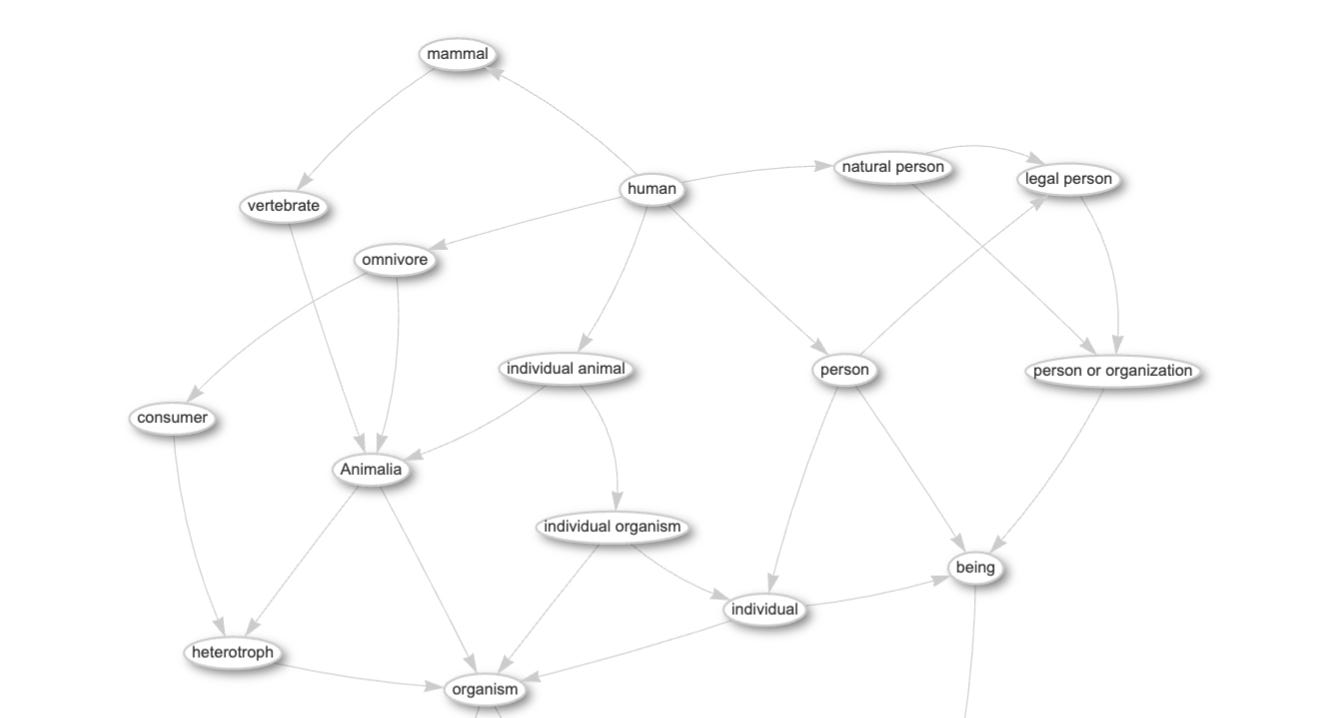

Hierarchical structures add the first layer of explicit relationship—containment or subsumption. A folder contains files. A category includes subcategories. A broader term encompasses narrower terms. Hierarchies are powerful because they’re intuitive—humans naturally think in hierarchies—and because they support inheritance. If Mammals are Animals, and Dogs are Mammals,’then dogs inherit animalness, without anyone having to state it explicitly. This is inference.

But hierarchies encode only one relationship type. Everything is either broader than, narrower than, or sibling to everything else. This constraint is sometimes a feature that is simple and predictable. And sometimes a hierarchy is a limitation—the world doesn’t organize itself as a tree.

A thesaurus extends hierarchies with additional relationship types. The classic thesaurus relationships—broader term (BT), narrower term (NT), and related term (RT) in SKOS—add the ability to say ‘these things are connected, with the added ability to say not only hierarchically.’ Alternative labels and hidden terms handle the lexical complexity of synonyms and preferred terms. Thesauri introduces the distinction between the concept and its labels. The same concept might have multiple lexical expressions (car, automobile, motor vehicle). This separation of semantic content from lexical form is a crucial step toward more sophisticated knowledge representation.

Additionally, with SKOS, we can represent that ‘cars’ and “roads’ are related without claiming one contains the other. A thesaurus allows us to declare that things are related without any further specificity. A Thesaurus can also express relationship types such as exact match, broad match, narrower match. Obviously, these relationship types are not very descriptive, but its more expressive than a strict hierarchy.

Ontologies take the leap into more complex relationship types. Instead of being limited to broader, narrower and related, an ontology can define any relationship the domain requires: ‘is manufactured by,’ ‘requires fuel type,’ ‘has seating capacity,’ ‘is competitor of.’ These relationships, represented as property relations or predicates, can have their own characteristics. Is the relationship symmetric? Transitive? Does it have cardinality constraints? Can it be inherited?

Ontologies also formalize the types of things that can participate in relationships. A ‘person’ can be ‘employed by’ an ‘organization.’ A ‘document’ can be ‘authored by’ a ‘person.’ These constraints—called domain and range constraints—make the knowledge representation more rigorous and enable automated reasoning. If the system knows that only persons can be authors, and something is listed as an author, the system can infer that thing is a person.

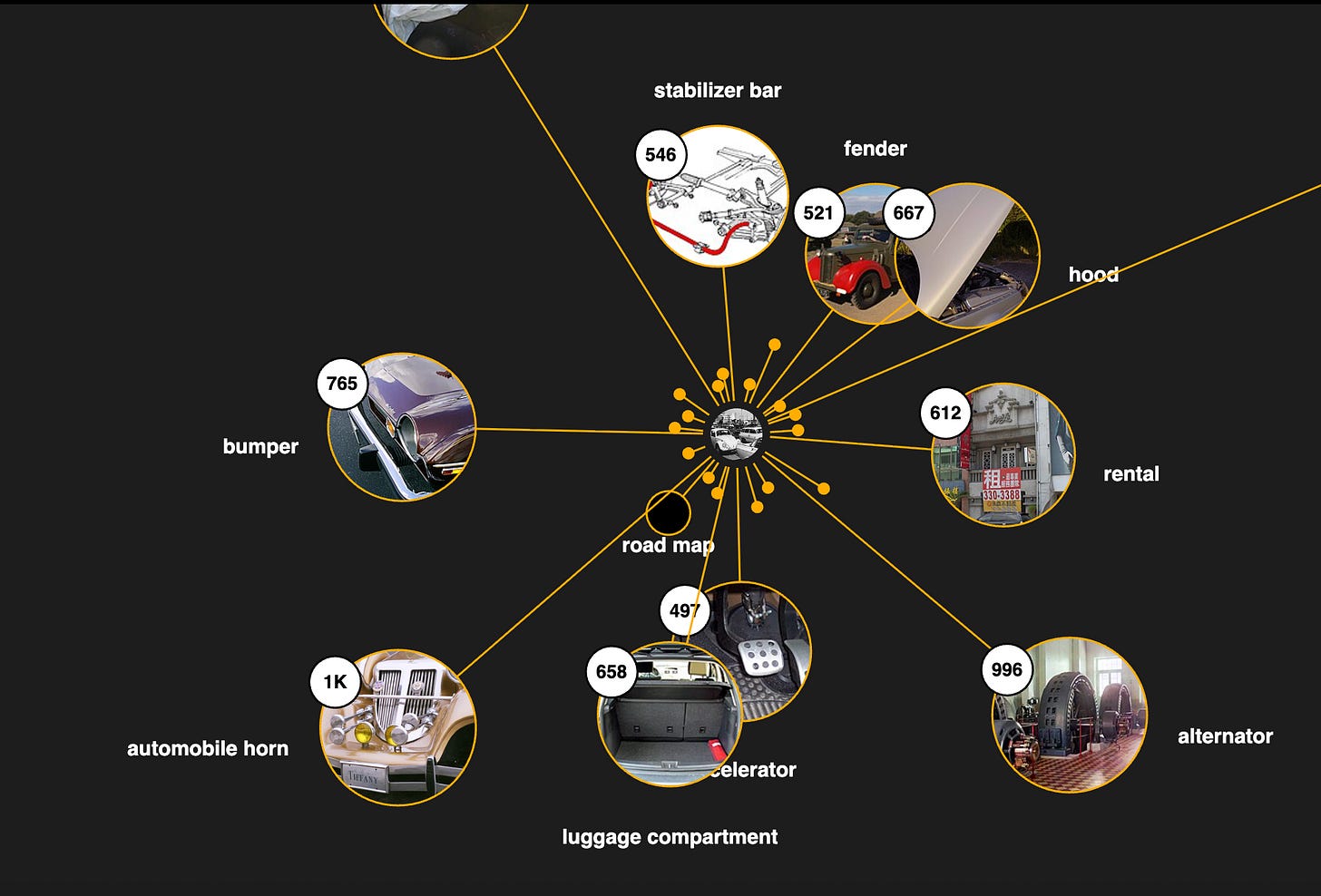

Knowledge graphs are ontologies brought to life with instance data. Where an ontology might define that ‘Person’ can have relationship ‘worksFor’ to ‘Organization,’ a knowledge graph actually instantiates: ‘Jessica’ ‘worksFor ‘Contextually’ . Knowledge graphs combine the structural richness of ontologies with the scale of databases. They’re how Google understands that when you search for ‘Obama height,’ you want a fact about a specific person, not a document containing those keywords.

The AI—Relationship Paradigm

Large language models are extraordinarily good at pattern matching across text. They can produce fluent prose about almost anything. But they don’t inherently know things in the way a knowledge graph knows things. They don’t have explicit representations of entities and relationships that can be queried, validated, and reasoned over.

This is why AI systems hallucinate. They generate plausible sounding text without grounded knowledge of what entities exist, how they’re related, and what constraints govern those relationships.

Every knowledge structure I’ve described—from simple hierarchies to rich ontologies—represents efforts to make relationships explicit and symbolic. That explicitness is what AI systems lack and desperately need, for reliability and accuracy.

When we build a taxonomy, we’re creating a machine readable statement about how concepts in a domain relate to each other hierarchically. When we build an ontology, we’re encoding the rules that govern what kinds of relationships are possible and meaningful. When we populate a knowledge graph, we’re grounding abstract schemas in concrete facts.

Not all relationship types are equal and the same. But all relationship types are meaningful, with varying degrees of expressiveness.

Building With Relationships, Architecting Knowledge

Twenty-five years into my career, I find it both vindicating and exciting that knowledge organization principles have become essential infrastructure for artificial intelligence. The disciplines of controlled vocabulary construction, relationship modeling, and semantic clarity are essential for modeling knowledge, at scale. This is where I am hopeful. As more folks learn the fundamentals of organizing knowledge, the entire technology industry has the opportunity to collaboratively gain a foothold in the core principles of organizing.

The most daunting outlook rests on helping organizations understand that their AI ambitions require this kind of groundwork. You can’t build reliable AI on a foundation of inconsistent terminology, implicit relationships, and unexamined assumptions about how your domain concepts connect.

The relationships are already there, in your data, in your documents, in the minds of your experts. The hard work involves making these relationships explicit, rigorous, and machine-readable.

about me. I’m an information architect, semantic strategist, and lifelong student of systems, meaning, and human understanding. For over 25 years, I’ve worked at the intersection of knowledge frameworks and digital infrastructure—helping both large organizations and cultural institutions build information systems that support clarity, interoperability, and long-term value.

I’ve designed semantic information and knowledge architectures across a wide range of industries and institutions, from enterprise tech to public service to the arts. I’ve held roles at Overstock.com, Pluralsight, GDIT, Amazon, System1, Battelle, the Oregon Health Authority, and the Department of Justice and most recently, Adobe. I built an NGO infrastructure for Shock the System, which I continue to maintain and scale.

Throughout the years, I’ve worked a bunch at GLAM organizations (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums), including the Smithsonian Institution, The Shoah Foundation for Visual History, Twinka Thiebaud and the Art of the Pose, Nritya Mandala Mahavihara, the Shogren Museum, and the Oregon College of Art and Craft.

And through it all, I am a librarian.