Where Provenance Ends, Knowledge Decays

I am an AI realist, not a skeptic. I work with AI systems every day. I build the knowledge infrastructure that makes them useful. I understand what large language models can do, and I appreciate their capabilities—genuinely. But I am also a practitioner with over 25 years in information architecture and semantic engineering, and I am telling you that we have a serious structural problem that almost nobody in the AI industry is talking about honestly.

LLMs strip provenance from knowledge. Systematically, architecturally and by design. And in so doing, AI systems are creating a form of knowledge network decay that degrades the knowledge infrastructures that human civilization rely upon.

What is Provenance?

The word Provenance is derived from the French word, provenir, which means to come from or forth.1 A 2025 LIS scholarly paper and literature review of information science papers defines provenance as “the story of how something came to be”. 2 The same paper includes other definitions of provenance:

The origin or source of something—Society of American Archivists (Gilliland-Swetland, 2000).

The history of the ownership of a work of art or an antique, used as a guide to authenticity or quality; a documented record of this (Oxford English Dictionary).

The chronology of the origin, development, ownership, location, and changes to a system or system component and associated data. It may also include personnel and processes used to interact with or make modifications to the system, component, or associated data—NIST (Joint Task Force, 2017).

Tracing provenance serves primarily to authenticate an object or entity by reconstructing its documented history — particularly the succession of ownership, custody, and storage locations that connect it back to its point of origin or discovery.

While comparative analysis, expert assessment, and scientific testing can support authentication, provenance is fundamentally a practice of documentation: assembling the contextual and circumstantial evidence that establishes legitimacy through an unbroken chain of record. The English usage of the term dates to the 1780s, and is closely analogous to the legal concept of chain of custody.

The Roots of Provenance

Provenance is one of the oldest, continuous knowledge management principles. To understand how human beings organize reliable knowledge, you have to go back further than the internet, further than computers, further than the modern library.

The formal articulation of provenance as an organizing principle dates to 1841, when the French Ministry of Public Instruction issued regulations requiring respect des fonds—that records be grouped by their creating entity rather than rearranged by subject.

The principle of des fonds received its most rigorous treatment in 1898, when Dutch archivists Samuel Muller, Johan Feith, and Robert Fruin published the Manual for the Arrangement and Description of Archives, which established provenance and original order as foundational to archival practice.3 As the archival historian Peter Horsman has noted, the Manual provided the first systematic description of provenance as a principle for both arrangement and description, arguing that original order is an essential trait of archival integrity.4

In the English-speaking world, Sir Hilary Jenkinson’s 1922 Manual of Archive Administration framed provenance as what he called the “physical and moral defense of the record”—an unbroken chain of custody that guarantees the integrity and authenticity of knowledge.5 For Jenkinson, the primary responsibility of archivists was to maintain what he described as “an unblemished line of responsible custodians.”6 Records derive their evidentiary value from their provenance. Strip the chain of custody and you lose the basis for trusting what the record says.

Provenance, critically, is not only about individual records. It is also about the relationships between records. As the archivist Genna Duplisea explains, original order preserves what archival theory calls the archival bond—“the interrelationships between records that were created during the same activity or function.” Maintaining original order, Duplisea writes, helps users “understand how the creator thought, worked, and grouped information.” 7

The concept, first formalized by Giorgio Cencetti in 1939, captures the essence of the critical importance of provenance: knowledge does not exist as isolated units. It exists in structured relationships, and those relationships are themselves carriers of meaning. Destroy the relationships and intelligibility is lost.

Theodore Schellenberg, writing from the U.S. National Archives in the 1950s, extended this framework by distinguishing between the primary values of administrative, legal, fiscal records and their secondary values, both evidential and informational.8 As Schellenberg put it, “the archivist must take into account the entire documentation of the agency that produced them.”9 Both types of value depend on provenance and both become meaningless without it.

The historian Peter Burke, in What is the History of Knowledge? (2016), situates this principle within a broader intellectual context. Burke argues that to qualify as “knowledge,” items of information must be discovered, analyzed, and systematized—what he calls, Verwissenschaftlichen, the shift towards a more scientific approach.10

Burke posits that knowledge is not raw data. It is information that has been processed through systems of verification, classification, and contextual placement. The mechanisms of that processing—and their history—are themselves a form of knowledge. Burke further argues that even the idea of scientific objectivity—“an attempt to separate knowledge from the knower”—has a history.11 Provenance is how we preserve the record of that processing. Without it, we collapse knowledge back into unverified assertion.

The Council on Library and Information Resources makes the stakes explicit: “The quest for knowledge rather than mere information is the crux of the study of archives… All the key words applied to archival records—provenance, respect des fonds, context, evolution, inter-relationships, order—imply a sense of understanding, of ‘knowledge,’ rather than the merely efficient retrieval of names, dates, subjects, or whatever, all devoid of context, that is ‘information.’”12

The Founding Logic of the Web

Here is what makes this especially painful. The World Wide Web was designed, from its inception, to preserve provenance. Tim Berners-Lee’s architecture was built on the URI—the Universal Resource Identifier—which is fundamentally a provenance mechanism. Every resource has a unique, persistent name. That name encodes ownership and origin. It can be followed to its source. The entire hyperlink structure of the web is, at its core, a provenance network: a system of traceable connections between claims and their origins.

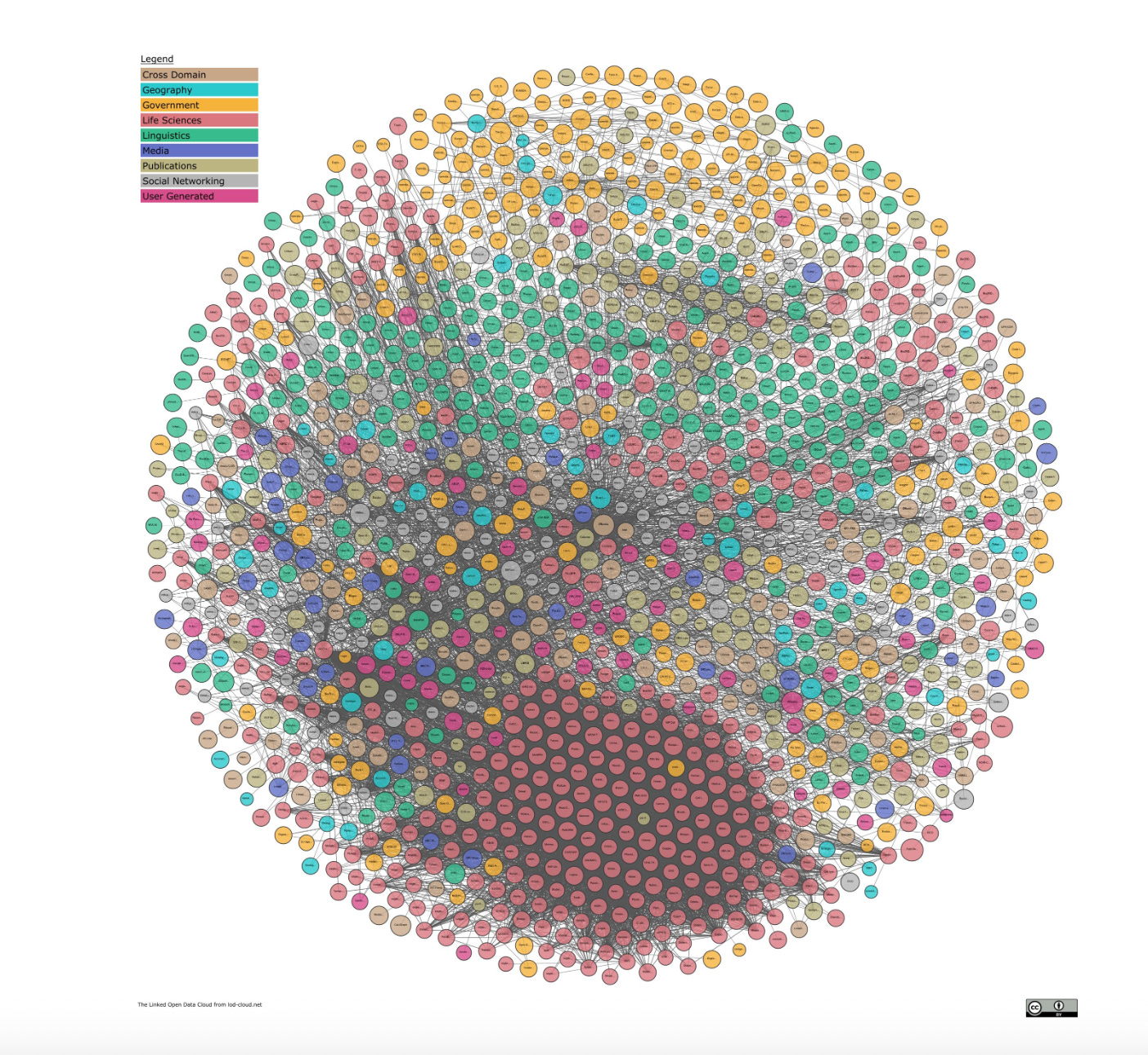

Berners-Lee made this explicit in his 2001 Scientific American article with James Hendler and Ora Lassila, laying out the vision for the Semantic Web.13 The article describes a web in which “information is given well-defined meaning, better enabling computers and people to work in cooperation.”14

The core architecture they proposed—RDF for structured assertions, ontologies for defining relationships between concepts, URIs for ensuring that every concept ties back to a unique, discoverable definition—is a provenance architecture. It was designed so that “using a different URI for each specific concept” would prevent semantic collapse, where a word means one thing in one context and another thing elsewhere.15

Berners-Lee, Hendler, and Lassila saw clearly what would happen without this layer. They wrote: “Human language thrives when using the same term to mean somewhat different things, but automation does not.”16 Their solution was ontologies—formal definitions of concepts, relationships, and inference rules—that would allow machines to follow meaning back to its source, verify it, and reason about it. They envisioned agents that would exchange “proofs” of their reasoning—machines that could show their work, trace their conclusions back to their premises, and let other machines verify the chain. The Semantic Web was provenance infrastructure for the digital age.

And the Semantic Web architecture was founded on the premise of trust.

At his keynote at XML 2000, Berners-Lee described provenance as essential to trust on the Semantic Web: digital signatures would establish “the provenance not only of data but of ontologies and of deductions.”17 The architecture explicitly required that “any piece of information has a context, so nothing has to be taken at face value.”

Trust was the architecture and design of the Semantic Web. A stark contrast to the architecture and design of foundational AI models.

Library Science Provenance and the Record

Library science has always understood that knowledge is not self-authenticating. The entire discipline exists because someone has to do the work of documenting where knowledge comes from, who produced it, under what authority, and how it relates to other knowledge. That is the very infrastructure of a library.

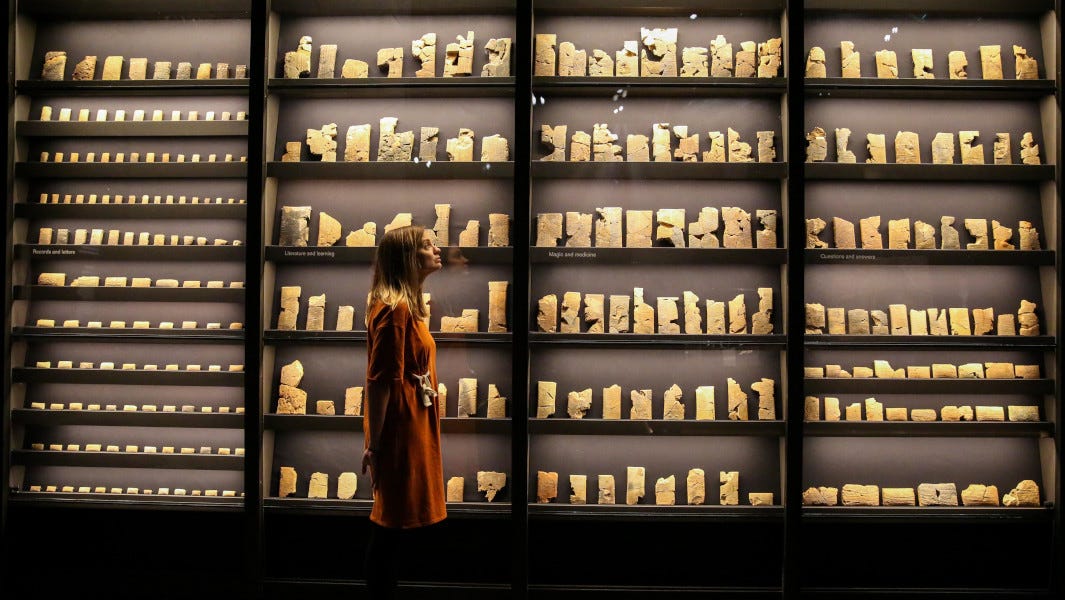

Suzanne Briet, librarian, historian and poet, in her 1951 manifesto What Is Documentation?, argued that a document is not simply a text — it is any piece of evidence organized to represent or prove something.18

An antelope in the wild is not a document. An antelope cataloged in a zoo, with a record of its capture, its species classification, its provenance of origin — that is a document. The act of documentation is what transforms raw existence into knowledge that can be evaluated, transmitted, and trusted. Without the record, there is no evidence. Without evidence, there is no knowledge — only assertion.

Patrick Wilson, writing on cognitive authority in Second-Hand Knowledge (1983), made a complementary point: we accept most of what we know not through direct experience but on the authority of others. The question is never simply what is claimed but who claims it, on what basis and the source of the claim.19 Wilson argued that the credibility of knowledge relies upon our ability to trace the lineage of information or a claim. And tracing works to their sources requires infrastructure and knowledge.

This is what the bibliographic apparatus was built to provide. Authority records establish the identity and credentials of creators. Catalog records document the publication history, edition, rights and institutional custody of resources. Citation conventions create explicit links between claims and the evidence supporting them.

Subject headings and classification systems organize knowledge into retrievable, navigable structures so that a researcher can move from a question to a source, from a source to its author and to that author’s citations. Every layer of this system is provenance infrastructure — designed to make knowledge findable and evaluable.

In library science, provenance is documentation. It is the chain of custody that connects a claim to its source, a source to its author, and an author to the context in which they produced knowledge. This chain is the mechanism by which knowledge becomes trustworthy. Large language models break this chain by design.

What LLMs Do to Knowledge

No major large language model maintains provenance in any architecturally meaningful way. Every LLM operates with two knowledge layers: a retrieval layer and a parametric layer. The retrieval layer — web search, retrieval-augmented generation, uploaded documents — can point to URLs and passages in real time. This is where citations come from when they appear.

Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok can all surface source links when their search features are enabled, with Gemini’s integration being the deepest: it uses “Grounding with Google Search” to cross-reference facts against live web results and provides clickable inline citations.20 Perplexity AI was designed from the ground up as a citation-first interface and comes closest to treating sourcing as a design requirement.

But the retrieval layer only tells you where the model looked, instead of where the model’s understanding came from. The parametric layer — the model’s trained weights, where the vast majority of its knowledge lives — is a provenance-free zone. During training, billions of documents are compressed, blended, and statistically distributed across billions of parameters. The process is lossy and irreversible. No metadata travels with the knowledge. No chain of custody is embedded in the weights. And the attribution graph does not survives the training pipeline. The information persists while the lineage does not.

RAG does not solve this. It addresses provenance for the retrieval step while leaving the deeper layer, the one that shapes how the model interprets, frames, and generates, entirely unattributed. As Hasan, Sion, and Winslett warned, data provenance tracking is essential for rights protection, regulatory compliance, and authentication of information21 and without secure provenance, history itself becomes forgeable.

Citation, Please

As Nicola Jones reported in Nature in January 2025, LLMs still struggle to produce accurate citations, frequently returning wrong authors or fabricating papers that don’t exist.22 This happens because of an LLM’s architecture. LLMs are next-token prediction engines. They optimize for coherence and plausibility, not factual accuracy, with no internal mechanism to verify whether a journal exists or a DOI resolves to anything real.

Lakera Research confirms that hallucination in citation generation is structurally linked to training data redundancy — highly cited papers get recalled with reasonable fidelity, while less prominent works are amalgamated into plausible-sounding fictions.23 The model doesn’t retrieve; it reconstructs. And in that reconstruction, lineage is lost.

What emerges is something worse than missing provenance — it’s false provenance. GPTZero coined the term “vibe citing” to describe how LLMs derive or combine real sources into uncanny imitations that appear accurate at first glance but collapse under verification.24 These fabricated references carry structural markers of legitimacy — author names, journal titles, volume numbers, DOIs — but point to nothing. They mimic the documentary chain of citations and footnotes without satisfying its duty in maintaining provenance.

And content with hallucinated citations become part of next generation AI training data. Yup.

Ghost references present with apparent legitimacy when indexed by systems like Google Scholar. This creates a feedback loop for LLMs, in which fabricated citations are discovered by other AI tools searching for verification in an already-polluted ecosystem. And without question, other AI systems will assume citations to be fact.

When LLMs are trained on content that presents false citations, the lies are adopted wholesale, and continue to proliferate, emerging as false facts in AI-generated output.25

This is knowledge network decay, in action.

The provenance infrastructure that scholarship, libraries and institutional memory were built to maintain is replaced by a convincing simulation of itself, one that looks like documentation but is not.

Backwards Land

LLMs do the opposite. They take carefully structured, semantically normalized, provenance-rich knowledge that human beings have created and compress it into statistical patterns. The controlled vocabulary collapses back into natural language while careful semantic distinctions dissolve. The relationships between terms, concepts, and their sources—the entire relational infrastructure that Svenonius describes—is vaporized during training.

A medical paper, produced through years of research and peer review, enters the training pipeline and is reduced to statistical signal. Its claims are blended with blog posts, press releases, Reddit threads, and content farms. The model has no mechanism for distinguishing between them. After training, those contributions are impossible to disentangle.

Longpre, Mahari, and their collaborators at MIT documented this problem with in their 2024 ICML paper. Current practices, they found, involve “widely sourcing and bundling data without tracking or vetting their original sources,” creator intentions, copyright and licensing status, “or even basic composition and properties.”26

And the consequences are real. The LAION-5B dataset—one of the most widely used text-to-image training sets—was removed from HuggingFace after thousands of images of child sexual abuse material were discovered within. Intellectual property disputes have triggered lawsuits against Anthropic, Stability AI, Midjourney, and OpenAI. These cases are the predictable result of building systems without provenance infrastructure.27

In September 2025, Anthropic agreed to pay $1.5 billion to settle a copyright infringement lawsuit brought by authors who alleged the company downloaded millions of copyrighted books from pirate sites like Library Genesis to train its language models — the largest publicly reported copyright recovery in history.28 The federal judge in the case ruled that AI training on legally acquired books qualified as fair use, but that acquiring those books through piracy did not.29 An ironic distinction that demonstrates how provenance matters for the legal legitimacy of the systems that consume it.

The industry calls this hallucination, as though it is an anomaly. It is not. The model is always doing the same thing: generating probable sequences of tokens. It has no internal state that distinguishes “recalling a fact” from “inventing a fact.” Hallucination is guaranteed by the architecture.

Provenance Was a Research Priority

The irony deepens when examining computer science which, as a discipline, has spent decades developing provenance systems. Cheney, Chong, Foster, Seltzer, and Vansummeren, in their 2009 paper for OOPSLA, defined the challenge directly:

Science, industry, and society are being revolutionized by radical new capabilities for information sharing, distributed computation, and collaboration offered by the World Wide Web. This revolution promises dramatic benefits but also poses serious risks due to the fluid nature of digital information. One important cross-cutting issue is managing and recording provenance, or metadata about the origin, context, or history of data.30

Pérez, Rubio, and Sáenz-Adán, in their 2018 systematic review of provenance systems published in Knowledge and Information Systems, surveyed 105 provenance systems across the research literature and identified a six-dimensional taxonomy of provenance characteristics: general aspects, data capture, data access, subject, storage, and non-functional aspects.31 Their review demonstrated that the field had already developed robust, well-characterized approaches to capturing, storing, and querying provenance at scale. So systems for verifying provenance do in fact, exist.

Werder, Ramesh, and Zhang, writing in 2022 in ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems, made the connection to AI explicit. They argued that data provenance—“a record that describes the origins and processing of data”—is essential for responsible AI systems.32 Their framework identifies four characteristics that AI systems must exhibit to avoid “disastrous outcomes”: fairness, accountability, transparency, and explainability. All four depend on provenance. 33 All four are structurally absent from LLMs as currently designed.

What’s most alarming? The computer science community had already identified provenance as a critical infrastructure requirement for trustworthy computation. The archival community had established it as a foundational principle for over a century. The Semantic Web community had built standards for implementing it at global scale. And the AI industry built systems that systematically destroy it.

Hardinges, Simperl, and Shadbolt, writing in the Harvard Data Science Review in 2024, frame the transparency deficit in stark terms. Access to information about training data, “is vital for many tasks”—yet “there remains a general lack of transparency about the content and sources of training data sets.”34

Hardinges et al. document how companies like OpenAI have explicitly refused to disclose dataset construction details, citing competitive concerns—a decision that leading researchers have wholly criticized.35 The authors draw a telling parallel to corporate financial transparency requirements that date back to the 1800s in the UK, arguing that standardized training data reporting should be no more controversial than standardized financial reporting. The infrastructure of accountability, they note, requires disclosure and standardized, interoperable documentation.36

Knowledge Network Decay

Knowledge does not exist in isolation. It exists in networks. A claim in a medical paper is connected to the methodology that produced it, the prior art, the datasets it analyzed, the peer review process it survived, the citation history that shows how the field received the research. These connections are what make the claim evaluable. Strip them away and you have assertion floating free of its cognitive context.

And this is what I mean by knowledge network decay. LLMs sever every one of these connections, systematically, for every piece of knowledge they ingest. And because LLMs are increasingly mediating how people encounter information—through search, through chatbots, through AI-assisted writing, through automated summaries—this severance is happening at scale.

Now compound this with recursion. LLM-generated content is flooding the internet. That content becomes training data for the next generation of models. Researchers call this model collapse, but the statistical degradation is only part of the problem. The knowledge degradation is worse: each cycle further dilutes the already-severed connections to original sources. Provenance decay compounds over generations.

Let's think about this concretely. A food safety scientist publishes a sourced guideline on safe canning temperatures, citing USDA research and documented botulism cases. An LLM ingests it, strips the provenance, and paraphrases it in response to a home canner's query. That answer gets posted to a forum — no citations, no methodology. The forum post becomes training data. The temperatures might survive intact, or they might drift. But even if the numbers hold, the provenance is gone. No one downstream can verify whether the guidance accounts for altitude, acidity, or jar size — because the chain of custody has been severed.

In information science, we would call this a catastrophic failure of collection integrity. Jenkinson would recognize it immediately: the “unblemished line of responsible custodians” has been broken.37 We are watching the rational equivalent of an archive losing its finding aids, its catalog records, its chain of custody documentation because of the architecture. The documents are still there, well, sort of. Just they have been stripped of every marker that tells you whether to believe them.

The Philosophical Foundation

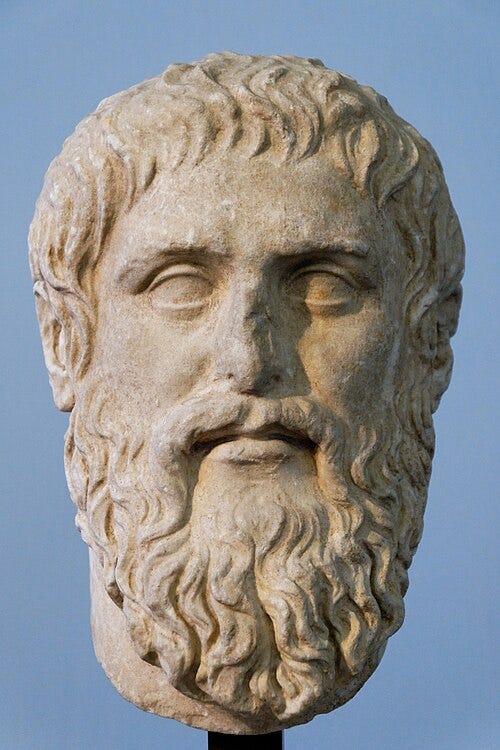

The philosophical tradition of knowledge has always understood that justification matters. Plato drew the line between knowledge and true belief in his Socratic dialogue, Theaetetus. Considered one of the first documented attempts to grapple with human knowledge, the work argues that knowledge is more than perception, that knowledge requires more than stated truth. And in order for something to be truth and therefore there must be an account of why it is true. Truth and knowledge exist because there is a chain of reasoning, evidence, and warrant that connects beliefs to the real world.38

Burke, in his treatment of the history of knowledge, emphasizes that the very act of organizing information is part of existing or eventual knowledge. The catalogues, the collection, in addition to the the analyzing, disseminating, and employing of information. This is where he identifies Verwissenschaftlichen or systematization to argue that information becomes knowledge only through processes of verification and critical analysis.39 For me, it’s a showstopper.

Burke’s insight—that even the idea of scientific objectivity has a history, and is exactly why stripping provenance is not a neutral act. It is the destruction of epistemic context.

Provenance is how we reason and justify, in order to arrive at truth and knowledge. When a librarian evaluates a source, they are asking whether the belief in question has adequate warrant. When an archivist traces a chain of custody, they are establishing the conditions under which we can trust what a record says. Berners-Lee understood this when he built the web around URIs.

LLMs produce outputs that appear to have justified knowledge. They sound authoritative, they use appropriate vocabulary, they mimic the cadence of expertise—but they carry no justification whatsoever. There is no warrant. There is no chain of reasoning connected to evidence. This is the production of unjustified belief at an industrial scale.

And the danger is that most people cannot tell the difference. Because the surface looks right. All the signals that humans use to evaluate credibility—signals that evolved in a world where fluent, authoritative speech was correlated with actual knowledge—are now being produced by systems that have no knowledge at all, in any philosophically meaningful sense.

Knowledge Decays

I studied history before I studied library science, and the combination of those two disciplines has given me an uncomfortable clarity about what happens when provenance disappears.

Here’s the thing. History is what survives of the past — the records, the chains of custody, the documented relationships between events and lived experiences of participants. Historians work with what was written down, preserved, attributed, and transmitted with enough documentary integrity that later generations can evaluate its reliability. When that chain breaks, history becomes incomplete, fragmented and less reliable.

This is the defining condition of most of human history. We know that medieval courts issued executions. We have traces — a decree, a name, a date scratched into an artifact. For medieval history we have the record : the testimony, the reasoning, the social and political pressures that shaped the outcome. We have the fact of the event, stripped of the knowledge that would make it comprehensible. The provenance was lost — not through malice, but through the accumulated failures of custody, transcription, and institutional memory over centuries. What remains are fragments, and from fragments we can only speculate.

Cheney et al. warned in 2009 that provenance — a record of the derivation history of scientific results — is critical for supporting reproducibility, result interpretation, and problem diagnosis.40 They saw provenance as a central requirement for emerging digital infrastructures.

Hasan, Sion, and Winslett framed the stakes even more bluntly: in science, medicine, commerce, and government, data provenance tracking is essential for rights protection, regulatory compliance, management of intelligence and medical data, and authentication of information.41 Without secure provenance, they argued, history can be forged . Not in the dramatic sense of falsified documents, but structurally, so that a record cannot be verified because the chain connecting them to their origins has been severed.

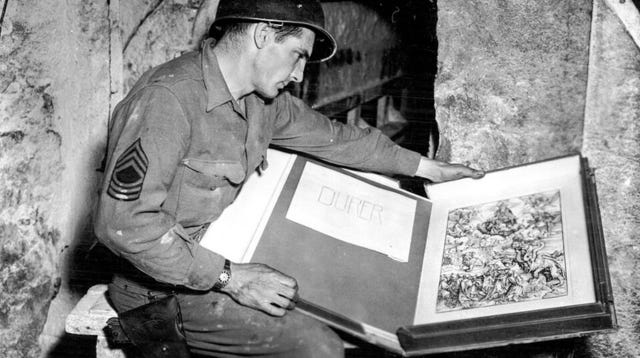

Rother, Mariani, and Koss demonstrated what provenance makes possible when it is preserved. Working with the Art Institute of Chicago’s collection data, they showed that provenances are ledgers containing the ownership and, to some extent, custody histories of artworks42— and that when those ledgers are structured and analyzed at scale, they reveal patterns of wealth, gender, power, and cultural value formation that would otherwise remain invisible.

By documenting a multiplicity of human activities relating to a specific class of goods, provenances are representations of complex social and economic relations and contexts. A single provenance chain for a Picasso painting revealed artist-dealer relationships, the geography of cultural capital shifting from Paris to New York, gendered patterns of inheritance, and the role of museum acquisitions in canon formation.

That knowledge exists only because the documentary chain survived intact. Sever any link, and the downstream analysis collapses.

Hurley, McKemmish, Reed, and Timbery, writing in Archival Science, explored the meaning of provenance in its broader social and organizational context through a records continuum lens43 — arguing that provenance is a tool of power. The ones to create the record and the record custodians preserve and erase the context. And the consequences of these decisions can ripple across generations. When provenance is narrowly applied in practice44, entire communities lose the ability to document their own history on their own terms.

What Knowledge Decay Looks Like

This is what knowledge decay looks like. Not burning libraries, but a slow, structural dissolution of the connections between claims and their sources, between knowledge and the authority that produced it. LLMs accelerate this process to an unprecedented scale.

Every time a model ingests a carefully documented claim, strips its provenance, and regenerates it as unattributed text, it replicates the exact mechanism by which historical knowledge has always been lost — only now it happens millions of times a day, across every domain, at machine speed.

When provenance disappears, the connection between expertise and recognition that sustains independent intellectual work is severed. LLMs do not neutrally distribute knowledge. They redistribute it, stripping it of the credit structures that incentivize its production. The result is not a democratization of knowledge. It is a flattening — a condition in which all claims carry equal weight because none carry any provenance.

Cant help but think twenty years into the future. Will knowledge survive? Cause If we continue to build systems that consume provenance and output plausibility we are engineering the decay of knowledge.

about me. I’m an information architect, semantic strategist, and lifelong student of systems, meaning, and human understanding. For over 25 years, I’ve worked at the intersection of knowledge frameworks and digital infrastructure—helping both large organizations and cultural institutions build information systems that support clarity, interoperability, and long-term value.

I’ve designed semantic information and knowledge architectures across a wide range of industries and institutions, from enterprise tech to public service to the arts. I’ve held roles at Overstock.com, Pluralsight, GDIT, Amazon, System1, Battelle, the Oregon Health Authority, and the Department of Justice and most recently, Adobe. I built an NGO infrastructure for Shock the System, which I continue to maintain and scale.

Throughout the years, I’ve worked a bunch at GLAM organizations (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums), including the Smithsonian Institution, The Shoah Foundation for Visual History, Twinka Thiebaud and the Art of the Pose, Nritya Mandala Mahavihara, the Shogren Museum, and the Oregon College of Art and Craft.

And through it all, I am a librarian.

Footnotes

Wikipedia contributors. (2026, January 4). Provenance. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23:09, February 12, 2026, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Provenance&oldid=1331138535

Bettivia, R., Cheng, Y.-Y., & Gryk, M. R. (2026). Usage of the term provenance in LIS literature: An Annual Review of Information Science and Technology (ARIST) paper. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 77(1), 92–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.25015

Muller, S., Feith, J.A., & Fruin, R. Manual for the Arrangement and Description of Archives (1898). English translation by Arthur H. Leavitt, 1940.

Horsman, P. “The Last Dance of the Phoenix, or The De-discovery of the Archival Fonds.” Archivaria 54 (2002): 1–23.

Jenkinson, H. A Manual of Archive Administration (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1922; 2nd ed. 1937).

Jenkinson, A Manual of Archive Administration, 11.

Duplisea, G. “Provenance and Original Order: Why They Matter in Archives.” Backlog: Archivists & Historians (July 9, 2025). https://www.backlog-archivists.com/blog/provenance-and-original-order.

Schellenberg, T.R. Modern Archives: Principles and Techniques (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956).

Schellenberg, Modern Archives, 16.

Burke, P. What is the History of Knowledge? (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016), 45.

Burke, What is the History of Knowledge?, 45–46.

Council on Library and Information Resources, “The Archival Paradigm: The Genesis and Rationales of Archival Principles and Practices,” CLIR Publication 89 (2000).

Berners-Lee, T., Hendler, J., & Lassila, O. “The Semantic Web.” Scientific American 284, no. 5 (2001): 34–43.

Berners-Lee, Hendler, & Lassila, “The Semantic Web,” 37.

Berners-Lee, Hendler, & Lassila, “The Semantic Web,” 40.

Berners-Lee, Hendler, & Lassila, “The Semantic Web,” 39.

Berners-Lee, T. “The Semantic Web.” Keynote address, XML 2000 Conference.

Briet, Suzanne. What Is Documentation? Translated and edited by Ronald E. Day and Laurent Martinet. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006. Originally published as Qu’est-ce que la documentation? Paris: Éditions Documentaires Industrielles et Techniques, 1951.

Wilson, Patrick. Second-Hand Knowledge: An Inquiry into Cognitive Authority. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983.

Fello AI. “Best AI Models In January 2026: Gemini 3, Claude 4.5, ChatGPT (GPT-5.2), Grok 4.1 & Deepseek.” January 9, 2026. https://felloai.com/best-ai-of-january-2026/

Hasan, Ragib, Radu Sion, and Marianne Winslett. “Preventing History Forgery with Secure Provenance.” ACM Transactions on Storage 5, no. 4 (2009): 12:1–12:43. https://doi.org/10.1145/1629080.1629082

Jones, Nicola. “AI hallucinations can’t be stopped — but these techniques can limit their damage.” Nature 637, 778–780 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00068-5

Kim, et al. “Hallucinate or Memorize? The Two Sides of Probabilistic Learning in Large Language Models.” Preprint at arXiv, https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.08877 (2025). Establishes the structural link between citation count as proxy for training data redundancy and hallucination rates.

Adams, Alex / GPTZero. “GPTZero finds 100 new hallucinations in NeurIPS 2025 accepted papers.” GPTZero Research Blog, January 2026. https://gptzero.me/news/neurips/ Introduces the term “vibe citing.”

Tay, Aaron. “Why Ghost References Still Haunt Us in 2025 — And Why It’s Not Just About LLMs.” Substack, December 22, 2025. Documents the feedback loop between fabricated citations and Google Scholar’s indexing infrastructure.

Longpre, S., Mahari, R., Obeng-Marnu, N., Brannon, W., South, T., Gero, K., Pentland, S., & Kabbara, J. “Data Authenticity, Consent, & Provenance for AI Are All Broken: What Will It Take to Fix Them?” Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), PMLR 235 (2024). arXiv:2404.12691.

Longpre et al., “Data Authenticity, Consent, & Provenance for AI Are All Broken,” 2.

Nadworny, Elissa. “Anthropic settles with authors in first-of-its-kind AI copyright infringement lawsuit.” NPR, September 5, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/09/05/nx-s1-5529404/anthropic-settlement-authors-copyright-ai

Kluwer Copyright Blog. “The Bartz v. Anthropic Settlement: Understanding America’s Largest Copyright Settlement.” Wolters Kluwer Legal & Regulatory, 2025. https://legalblogs.wolterskluwer.com/copyright-blog/the-bartz-v-anthropic-settlement-understanding-americas-largest-copyright-settlement/

Cheney, J., Chong, S., Foster, N., Seltzer, M., & Vansummeren, S. “Provenance.” Proceedings of OOPSLA ’09 (ACM, 2009). doi:10.1145/1639950.1640064.

Pérez, B., Rubio, J., & Sáenz-Adán, C. “A Systematic Review of Provenance Systems.” Knowledge and Information Systems 57 (2018): 495–543. doi:10.1007/s10115-018-1164-3.

Werder, K., Ramesh, B., & Zhang, R. “Establishing Data Provenance for Responsible Artificial Intelligence Systems.” ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems 13, no. 2 (2022): 22:1–22:23. doi:10.1145/3503488.

Werder, Ramesh, & Zhang, “Establishing Data Provenance for Responsible AI Systems,” 22:2.

Hardinges, J., Simperl, E., & Shadbolt, N. “We Must Fix the Lack of Transparency Around the Data Used to Train Foundation Models.” Harvard Data Science Review, Special Issue 5 (2024). doi:10.1162/99608f92.a50ec6e6.

Hardinges, Simperl, & Shadbolt, “We Must Fix the Lack of Transparency,” 2–3.

Hardinges, Simperl, & Shadbolt, “We Must Fix the Lack of Transparency,” 4.

Stapleton, R. “Jenkinson and Schellenberg: A Comparison.” Archivaria 17 (1983): 75–85.

Chappell, Sophie-Grace and Francesco Verde, “Plato on Knowledge in the Theaetetus“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2025 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2025/entries/plato-theaetetus/>.

Burke, What is the History of Knowledge?, 45.

Cheney, James, Stephen Chong, Nate Foster, Margo Seltzer, and Stijn Vansummeren. “Provenance: A Future History.” In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGPLAN Conference Companion on Object Oriented Programming Systems Languages and Applications (OOPSLA ‘09), 957–964. ACM, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1145/1639950.1640064

Hasan, Ragib, Radu Sion, and Marianne Winslett. “Preventing History Forgery with Secure Provenance.” ACM Transactions on Storage 5, no. 4 (2009): 12:1–12:43. https://doi.org/10.1145/1629080.1629082

Rother, L., Mariani, F. & Koss, M. (2023). Hidden Value: Provenance as a Source for Economic and Social History. Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte / Economic History Yearbook, 64(1), 111-142. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbwg-2023-0005

Rother, Lynn, Fabio Mariani, and Max Koss. “Hidden Value: Provenance as a Source for Economic and Social History.” Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte / Economic History Yearbook 64, no. 1 (2023): 111–142. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbwg-2023-0005

Hurley, Chris, Sue McKemmish, Barbara Reed, and Narissa Timbery. “The Power of Provenance in the Records Continuum.” Archival Science 24 (2024): 825–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-024-09463-9

Your analysis of provenance as a structural condition of knowledge—rather than a mere archival technique—touches a deeper ontological fault line in current AI systems. The problem, as you frame it, is not simply that sources are lost, but that the generative architecture itself dissolves the relational fabric through which knowledge acquires legitimacy, continuity, and intelligibility.

In my own philosophical work on event and temporality, I approach a related question from a different angle: knowledge is not a static object that carries provenance as an external attribute, but an event emerging within a structured field of relations. When those relations are reduced to probabilistic patterning without preserving their formative dynamics, what decays is not only attribution, but the very ontological coherence of what counts as knowledge.

I believe that part of the solution may lie in rethinking knowledge infrastructures in explicitly event-relational terms—where temporal emergence, structural dependency, and generative linkage are modeled as intrinsic rather than supplementary features. Provenance, in such a framework, would not be appended metadata but a trace of the constitutive processes that bring knowledge into presence.

The challenge, then, may not be merely to reattach sources to outputs, but to redesign our systems so that the dynamics of formation remain structurally legible.

A marvelous article, and I learned so much. I only have one nit to pick. You say:

"…the retrieval layer only tells you where the model looked, instead of where the model’s understanding came from. The parametric layer — the model’s trained weights, where the vast majority of its knowledge lives — is a provenance-free zone"

The model has no understanding. For the model there is no knowledge. We mistake plausible structures of tokens for understanding or even infirmation, only because these structures resemble artifacts of understanding or information. There's no substitute for the real thing. We must not loose the distinction, nor shoukd we ignore the active role human understanding plays (and is appropriated) in granting these machines powers they don't have.

Thank you very much for the clarity you bring!